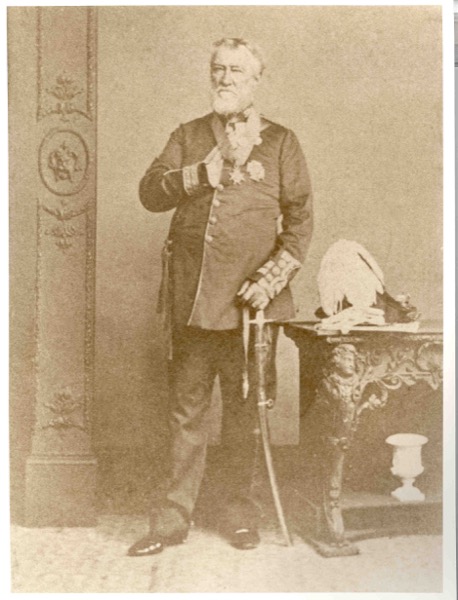

Lieutenant-General Sir George Cornish Whitlock, K.C.B.

In the last century the army of the Madras Presidency held a foremost place in the achievement of the grand roll of victories by which our Indian empire was established. We need only point to the names emblazoned on the colours of the old Madras Fusiliers – now known in Her Majesty’s service as the 102nd Royal Madras Fusiliers – such as “Arcot,” “Plassey,” “and many others, to bring back to mind the glorious deeds of Clive, while the colours of numerous native infantry regiments bear on their folds the word “Seringapatam,” recalling the brilliant feat of arms by which Lord Harris earned his peerage, and the power of the most formidable army we had, up to that time, encountered in the East, was finally annihilated.

In those days, and down to the Mahratta war of 1818, when Malcolm crushed the Peishwa at Mahidpore, and the first Burmese War of 1824, the Presidency of Fort St. George did the lion’s share of the fighting; but from the last-mentioned campaign to the present time, they have not had the same opportunities for earning that distinction in the field which is the aim of every man entering the profession of arms. It can be seen on reference to a map of India, that it was owing to the geographical position of the Madras Presidency that the Madrasees had no share in the wars of Afghanistan and Scinde, in the campaign of 1843 with Gwalior, and the two Sikh wars that followed in quick succession. They were in a measure indemnified for this inaction by sending troops to China in 1840-42, and to Burmah in 1852. But these were petty wars when compared with the gigantic struggles waged on the banks of the Sutlej and Chenaub, when British armies fought drawn battles, and British colours and guns fell into the hands of a foe the most warlike and stubborn we have yet encountered in the East. People got into the habit of speaking disparagingly of the great southern division of the Indian peninsula, and sneeringly dubbed it the “benighted Presidency”. But a day was at hand when British power in Asia had to encounter a storm before which the ship of state well-nigh foundered with all hands – all hands, that is to say, but those in the “benighted” Presidency, for the Madrasee native soldier, whom it was the fashion to decry as “low caste,” and deficient in the dash and military bearing of your Rajpoot, proved faithful to his salt in those troublous times. When the whole Bengal army rose in mutiny, when Bombay regiments in some instances joined them, or had to be disarmed, the patient Madrasee native soldier not only resisted every attempt to seduce him from his allegiance, but formed part of numerous columns, in some instances without European soldiers to watch them, that we despached all over the country to reconquer some portions, or hold points that had been lost through the treachery or sedition of the patted Bengalee. All the world knows what the gallant old Madras Fusiliers did under their noble chief Neill, than whom there was not, perhaps, a finer or truer soldier in India; but many are inclined to forget that the Madras Sepoy did good service to the State, and it was under Sir George Whitlock, himself a Madras officer, that they achieved their successes, and stamped out the fires of mutiny in Bundelcund.

George Cornish Whitlock was born in the year 1798, and was a son of George Whitlock, Esq., of Ottery St. Mary, in Devonshire, a county famous from before the times of Sir Walter Raleigh, for the great men it has reared for the country of which it forms so picturesque a portion. George Whitlock joined the Madras army – his commission as an Ensign bearing date 4th June, 1818 – and his name appears on the cadre of the 8th N.I., though he was attached to the Rifle corps of the Madras Presidency. On the 20th December in the same year, he was gazetted to his Lieutenancy, and was fortunate enough to see service before he had been twelve months in the army.

At the time of his arrival the Pindaree and Mahratta war was being carried on under the supreme direction of that good soldier and able diplomatist, Sir John Malcolm, G.C.B. India, as this time, boasted the possession of a galaxy of talent, reared in her own local service, such as she can scarcely ever hope to surpass, and as any country might be proud to call her own. I need not name such men as Sir Thomas Munro, Sir John Malcolm, Sir D. Ochterlony, Sir T. Metcalfe, and Mr. Mountstuart Elphinstone, to call forth the expression of a wish that the Government of Her Majesty and her royal successors may be served as well as was plain old “John Company,” not only then, but down to the day when, having reared the Lawrences and Montgomerys of the Indian mutiny – soldiers and statesmen who, with their noble band of assistants, saved an empire to Britain by the display of talent and virtue of the very highest order – this “Company of Merchants” handed over to the Crown intact this magnificent country, which they and their servants had converted into a British dependency in the space of a century.

Lieutenant Whitlock took part with his regiment in the concluding operations of the second Mahratta war. After the capture of Asserghur, by the troops under Sir John Malcolm, a field-force was organised out of General Doveton’s Reserve Division, under the command of Brigadier-General Prinzler, and was directed to operate against Copaul Droog. This force was composed of three troops of H.M.’s 22nd Light Dragoons, four troops of the 1st Native Cavalry; a strong detail of artillery with field-guns, and a battering train; and five regiments and detachments of infantry, of which the Rifle corps formed a part. On the 7th May, 1819, the division entered the territories of His Highness the Sudahdar of the Deccan, and, on the following day, encamped before Copaul Droog. On the garrison refusing to surrender, a heavy cannonade was opened on the fort, which mounted 18 pieces of ordnance, and, after five days’ continuous firing, the Engineer officers pronounced the breech practicable. Accordingly, on the morning of the 13th May, two columns of attack were formed, and moved out of the batteries at twelve o’clock.

The left attack moved on without much opposition till it arrived at the first gate, which was blown open by a “galloper” gun of H.M.’s 22nd Light Dragoons, which was brought into action through a heavy fire, up a road apparently impracticable for any wheeled carriages. The right attack found the wall they were to escalade very high, and General Pritzler detached the reserves, to follow up the left attack, when the whole of the three parties formed a junction at the second gateway, from which they pushed the enemy, who disputed every inch of ground, through the gates to the very summit of the hill, where they surrendered. The British loss was six killed, including an officer of the Rifle corps, and fifty-one wounded, the smallness of which, considering the strength of the enemy’s works, the General attributed to the spirited manner in which the officers and men did their duty.

This was the only operation of the Mahratta war in which Lieutenant Whitlock assisted. He was transferred to the 36th Madras N.I. in 1823, and took part in the Burmese War of 1824-26. Previous to embarking for foreign service, he had married Harriet, third daughter of Sir Samuel Toller, Judge-Advocate-General at Madras, by whom he had a large family. He was at this time adjutant of his regiment, and embarked with it from Madras, the division from which Presidency was stronger than that from Bengal, and consisted of three European and seven native regiments, with detachments of pioneers and artillery. This arose from the disinclination of the high-caste Bengal Sepoy to cross the “Kala Pawnee,” or black water, as they called the much-dreaded sea; while, on the other hand, the Madrasees vied with each other in their eagerness to be selected for foreign service. The entire force numbered 11,000 men, under the chief command of Sir Archibald Campbell, while Brigadiers-General Macbean and M‘Creagh led the Madras and Bengal columns respectively, though the former officer soon after gave place to General Fraser. Hostilities were declared on the 14th February, 1824, and peace was concluded on the second anniversary of that day, but not without considerable expenditure of treasure, and a vast sacrifice of life, chiefly owing to dysentery and the terrible Arracan fever, which not only carried off a fourth of the entire army, while half the survivors were in hospital, but laid the seeds of disease in many of those who escaped its immediate ravages. Nevertheless it is certain we never waged a more just war, for the contest was forced upon us by the arrogance of the king and court of Ava.

This arduous contest was not without its uses, for here Sir Robert Sale, Sir Henry Havelock, and Sir George Pollock earned distinction, and laid the foundations for that thorough acquaintance with the art of war which, in after years, stood them in such good stead at Jellalabad, Lucknow, and Afghanistan.

Whitlock’s regiment did not take a prominent part in the Burmese war. On the 16th July, 1831, he was gazetted to a Captaincy, after a service of just thirteen years. Captain Whitlock next saw service in Coorg. This principality lies on the Malabar coast, between Mysore and the sea, and comprises an area of about 1,500 square miles, with an elevation of 3,000 feet above the level of the sea. At the commencement of the war with Tippoo, in 1791, a treaty had been concluded with the Raja, which secured his assistance and the resources of his country against the common enemy, while the British Government guaranteed the independence of his small state. In 1809 our brave ally died, and was succeeded by his brother, who, on his decease in 1820, bequeathed the throne to his son, Vira Raja. His first act was to put to death all those who had thwarted his views before he came to the throne; and, to prevent the possibility of his being superseded, he caused his kinsmen, twelve in number, to be executed. He exhibited a peculiar hatred of the British Government, and prohibited all intercourse between his subjects and Englishmen, a course which for some time had the effect of concealing his conduct from observation. At length, in 1832, his sister and her husband fled for their lives, and revealed the hideous tale of his barbarities, to the British Resident at Mysore, who proceeded in person to the capital, and endeavoured, though without success, to bring the Raja to reason. After fruitless attempts at negotiation, Lord William Bentinck resolved to treat the tyrant as a public enemy, and issued a proclamation recounting his atrocities, and announcing that he had ceased to reign.

A force of about 6,000 men was directed to enter the country from the north, south, east, and west, in four separate columns, under the general command of Colonel Lindsay. The columns under the immediate order of this officer, consisted of H.M.’s 39th, four N.I. regiments, with eight guns and a detachment of sappers. Colonel Lindsay, who advanced on the capital of Coorg from the eastward, detached Colonel Stewart with part of his division to act independently. With the advanced guards of this column, marched Captain Whitlock in command of the light company of his regiment. Colonel Stewart’s force, which marched from Periapatam on the 1st April, 1834, crossed the Cauvery on the following day, and took a distinguished part in the capture of the fortified works on that river. On the 3rd, Captain Whitlock succeeded to the command of his regiment, owing to the absence of the Major, while employed as staff officer to the Brigadier, and, on the same day, he led the 36th Regiment against a stockade of great strength, known as Nunyarapettah, which commanded the road leading to the capital. The stockade was stormed in good style, and with but slight loss to the assailants. On the 5th, the column advanced to Rajendrapett, skirmishing on its march with the enemy amidst the jungles on either side, but without experiencing any serious loss, and, on the following day, entered Madhukaira, the capital of Coorg, upon the ramparts of which Colonel Lindsay had that morning hoisted the British ensign. The Coorgs displayed the utmost bravery in the resistance they made against the advance of the other divisions. Two of the British columns were repeatedly repulsed by these gallant hill-men, and many officers and more than 200 soldiers fell beneath their weapons. But the Raja was as cowardly as he was cruel, and, abandoning his capital, surrendered to General Fraser, the Political Agent, who issued a proclamation, annexing the territory of Coorg to the Company’s dominions, “in consideration of the unanimous wish of the people”.

On the recommendation of the Commissioner of affairs at Coorg, the Governor-General directed that Captain Whitlock should remain in command of his regiment, vacant by the death of the Major, and of the station of Mereara where it was quartered. Captain Whitlock subsequently served on the Divisional Staff as Deputy-Assistant Adjutant-General for a period of five years. On the 31st of July, 1840, he attained his majority, and, in 1848, was transferred to the 3rd N.I., much to the regret of his officers, who presented him with a service of plate in recognition of his uniform kindliness, and of their respect for him as commanding officer.

In 1853 he was selected by the Commander-in-Chief to raise the 3rd Madras European Regiment; and, having attained his Lieutenant-Colonelcy on the 22nd September, 1845, was appointed its first commanding officer. On the 20th June, 1854, he became a full Colonel, and was appointed Brigadier at Kurnool, in the Madras Presidency.

A time of stern trial for every European in India was fast approaching, and, in May 1857, the whole of the North-west Provinces was wrapped in the flames of revolt. Soon after his arrival in India, Sir Colin Campbell, the Commander-in-Chief, laid before Lord Canning, the Governor-General, a memorandum, bearing date 18th October, 1857, in which he submitted for his consideration a plan of operations for the pacification of Central India, and for ultimately co-operating with himself, if necessary, on the banks of the Jumna. His proposition was, in effect, that columns should be formed from the two Presidencies of Bombay and Madras; that from the former, under the command of Sir Hugh Rose, should march from Mhow to Gwalior and Jhansi, while that from the latter, which was to be led by Sir Patrick Grant, should march towards Nagpore, and be ultimately directed on Jubbulpore. These two columns were to act in concert. The Governor-General in Council adopted the arrangements suggested by Sir Colin Campbell, and, on the 13th November, instructions were despatched to the Madras Government. The following extract relates to the line of march:

“It is the wish of the Governor-General in Council that the force should be directed through the Nizam’s dominions to Nagpore, and eventually to Jubbulpore. Whether it will be necessary to call the force further beyond the Nerbudda to Saugor or elsewhere, is yet uncertain. It must depend upon the work which the column from Bombay may have in hand in Rajpootana, or in the western portion of Central India, after it shall have assembled in the month of January, and upon the course of events in Bundelcund, Central India, and Oudh, which may possibly occupy the force in Bengal, and make it necessary to leave the Saugor territory in the care of the Madras column. It is the desire of the Governor-General in Council not to draw that column further northwards than can be avoided, but it must be prepared to operate even beyond Saugor if required.”

In the meantime Mr. Plowden, the Commissioner of Nagpore, had made an application for assistance, and the Madras Government directed the organisation of a force for service in the Nagpore, Saugor, and Nebudda territories, and appointed Whitlock, who had attained the rank of Major-General in June, to the command. The only change effected on learning the wishes of the supreme Government was to make an addition to the force already constituted. The field-force, which had been hitherto known as the Kurnool moveable column, now consisted of two troops of horse artillery, three companies of field artillery, with two light field batteries attached; H.M.’s 12th Lancers, and the 6th and 7th Madras Light Cavalry; H.M.’s 43rd Light Infantry, the 3rd Madras Europeans, and the 1st, 5th, and 19th M.N.I.; with two companies of sappers. Brigadier W.H. Miller commanded the artillery; Alexander Lawrence, eldest brother of Henry and John Lawrence, commanded the cavalry; while the two brigadiers of infantry were T.D. Carpenter, of the Madras army, and J. McDuff, of the 74th Highlanders. In those days, when European soldiers were so scarce, this force seemed quite a respectable army.

The primary objective of this column was the relief of Saugor; but as the force could not be expected to reach that place till the middle of January, Major Erskine, the Commissioner of the Saugor division, applied for assistance to Sir Hugh Rose, the commander of the Central India field-force. Saugor, which is sometimes called the key of Central India, was certainly in a critical condition. It contained a large and valuable arsenal, and, at this time, was a refuge for some 150 women and children, who had taken shelter within the fort. The garrison was totally inadequate to stand a siege, and immediately outside the cantonments were 1,000 Bengal Sepoys, who, though they had not as yet exhibited any inclination to mutiny, were necessarily an object of suspicion and alarm. The surrounding district was in a state of the most lawless disorder, and the rebels were in possession of several strong forts in the neighbourhood, at Ratghur and Garrakotah, which Sir Hugh Rose subsequently captured. General Whitlock marched early in January, and, on the 10th, reached Kamptee, on the frontiers of the Saugor and Nerbudda territories; after remaining there a fortnight he started, on the 23rd, for Jubbulpore, a town on the Nerbudda, about 150 miles due north of Kamptee, which was reached on the 6th of February.

After a stay of a few days at Jubbulpore, General Whitlock proceeded north with his main column, by the Dekhan road to the fort of Jokahie, which had been captured by Lieutenant Osborne, with his Rewah levies, and thence to Dumoh, which he reached on the 4th March. At Jubbulpore he left behind the 50th N.I., under Colonel Keating, to protect the town and district. As his future contemplated operations were against various strongholds in the neighbourhood of Dumoh, he left there the main body of his force, and removed the headquarters of his division to Saugor, which had been relieved by Sir Hugh Rose on the 3rd of February. On the 13th of March General Whitlock quitted Saugor, leaving there a detachment of the 3rd Madras European Regiment and 50th Madras N.I., and returned to Dumoh. All necessary preparations were made to take the field in three different directions, when, on the 16th of March, instructions were received from the Governor-General, which changed all previous plans.

In the meantime, Sir Hugh Rose and General Whitlock had been keeping up a correspondence as to their doings and projected operations. Sir Hugh announced his intention of advancing, as speedily as possible, on Jhansi, so as to clear the left flank of Lord Clyde’s army, and suggested to General Whitlock to clear the valley of the Nerbudda, and also requested him to furnish him with transport for grain and pontoons. The order which General Whitlock received when near to Dumoh, on the 16th of March, and which changed all his plans, was to march to the relief of the loyal chiefs in Bundelcund. Before considering the consequences produced by this order, it will be desirable to give some account of the district destined for the scene of operations, and to state the circumstances which led to its being given.

Bundelcund is a territory about 200 miles in extent from S.E. to N.W., and 155 miles from S.W. to N.E. It is bounded on the west and northward by Gwalior, on the north-east by the Jumna, on the east by the Rewah, and on the south by the British territory of Saugor and Nerbudda. In the early part of the century Bundelcund was one of the territories under Mahratta rule; but, as we have seen, in 1819 the Mahratta power had been broken by the English, and the last Peishwa ceded to the East India Company all his rights in Bundelcund, and retired to Bithoor, a holy city on the Ganges, as a pensioner of the British government. He adopted as his successor Nana Sahib, but the British Government refused to recognise the title by adoption; and this refusal, no doubt, was the chief grievance of the Nana.

At this time the province of Bundelcund consisted partly of British districts, where the native sovereigns were only titular, and the judicial and fiscal management appertained to the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-west Provinces; and partly of native states, over which the Governor-General’s agent for Scindia’s dominions and Bundelcund exercise a political superintendence. Amongst the native states were Adjghur, Chirkaree, Chutteepore, Punnah, and Tehree. Jhansi, also, until a short time before the mutiny, had been a native state, but upon the death of the late Rajah, Lord Dalhousie refused to recognise a son whom he had adopted, and Jhansi was declared to have lapsed to the British Government. The Ranee, the Rajah’s widow, however, refused to acknowledge our right, and, on the mutiny breaking out, joined the rebel cause, and became one of its most active and implacable leaders.

Amongst the British districts of Bundelcund were Banda, Calpee, Hummeerpore, and Kirwee, otherwise called Tirohan, which is a part of Banda. The Nawab of Banda, upon the outbreak of the mutiny, seems to have saved the lives of the Europeans, but, subsequently, taking advantage of the disorder, attempted to assume the rule of the Hummeerpore district, collecting revenue, and forbidding, under pain of death, payment of revenue to the British, which was being collected for them by the Rajah of Chirkaree. The chiefs of Kirwee were two brothers, called Narrain Rao and Madho Rao, connections of Nana Sahib, both young men, and much under the influence of their prime minister, one Baboo Gobind. They, also, like the Nawab of Banda, were at first friendly to the British, but, towards the end of the year 1857, they conspired with him, advanced him money, shared the revenue which he unlawfully exacted, and took mutineers into their pay.

The most faithful ally to the British in Bundelcund was the Rajah of Chirkaree. In July, 1857, he had been invested by Mr. Carne – the assistant magistrate on duty at Chirkaree – with the management of the Hummeerpore district, and deputed to collect the revenue for the British Government. He was not, however, strong enough for this task, and became the object of attack by the enemies of the British, especially the Nawab of Banda and Nana Sahib. Towards the end of January, 1858, he was defeated at Belgaum by mutineers from Julalpore, and compelled to retreat to his capital, Chirkaree, where he expected daily to be attacked. Mr. Carne, through Major Ellis, applied for assistance from Sir Hugh Rose’s column; but Sir R. Hamilton – the political officer with the Central Indian column – found himself obliged to decline, and could only suggest the possibility of General Whitlock being able to help him. The Rajah of Chirkaree’s fears proved true.

On the 18th of February about 1,200 mutinous infantry and cavalry from Calpee, with ten or twelve guns, aided by 8,000 or 9,000 matchlock men and Sowars, came down upon Chirkaree and invested it. These assailants were, undoubtedly, the Gwalior Contingent, which had mutinied against the British, and were now in the Nana’s pay, and headed by his agent, the scarcely less notorious Tantia Topee. They were, shortly afterwards, reinforced by troops from the Nawab of Banda and the Ranee of Jeitpore. No assistance came from the British columns, and the besiegers obtained possession of the whole of the city of Chirkaree, the fort only holding out. In this emergency, Mr. Carne, on the 27th February, and again on the 1st March, wrote for aid direct to Mr. Edmondstone, the Secretary to the Governor-General at Allahabad. The Governor-General, however, in a letter, dated the 7th March, informed Mr. Carne that he could not afford assistance; but, altering his determination on the 13th, his lordship, through his Military Secretary, Colonel Birch, sent to General Whitlock, ordering him forthwith to proceed to the relief of the loyal chiefs of Bundelcund. While Sir Hugh Rose adhered to his original intention to move northwards on Jhansi – he had received, on the 30th March, Lord Canning’s approval of this step – General Whitlock quitted the Saugor and Nerbudda territory on the 22nd March, and entered Bundelcund, marching, in the first instance, in a north-easterly direction to Punnah, with the object of relieving the loyal Chirkaree chief, who was threatened at this time by a rebel army amounting, according to an estimate by Sir Robert Hamilton, to no less than 60,000 men.

On the 25th March, General Whitlock reached the right bank of the Kane river, and, on the 29th, arrived at Punnah, where he halted until the 2nd April. The immediate necessity to advance on Chirkaree, had, however, ceased, for Major Ellis, the Political Officer with the General, learned that, on the 19th – ten days before the arrival of the Madras column at Punnah – the rebels besieging Punnah had retired, and, having left the Rajah wholly unmolested, had collected in force near Nowgong. Nevertheless, General Whitlock resolved to march to Chirkaree, taking the route which would lead him in a north-westerly direction through the Punnah Ghaut. On the 2nd of April, the Madras force descended a very difficult pass, Murwa Ghaut, to a place called Mandala, close to the River Kane. There they were obliged to halt, in consequence of the baggage having been delayed; and, whilst halting, on the 3rd of April, an express came in from Sir Hugh Rose, dated the 30th March, requesting the force to move forward with all expedition direct on Jhansi. General Whitlock at once made every exertion to comply with this request; but, from the first, it was foreseen that it would be hardly possible for the column to move on again until the 5th. Before they could leave Mandala, there came further news that the rebels, who had been besieging Chirkaree, had marched across country to Nowgong, and thence advanced to attack Sir Hugh Rose under the walls of Jhansi, where they had been completely defeated, and were in full flight.

General Whitlock now altered his course, and, on the 7th, set off on his march to Banda. The Madras column reached Chutterpore on the 9th, and, on the following day, fought an action with the rebels at a place called Jheeghun. Having received information that 2,000 of the enemy, under a notorious rebel chief, called Disspat Bandala, had collected at this place, the depot for their plunder, distant about seventeen miles from Chutterpore, General Whitlock made a night march on the 9th April; but as, from the intricacies of the road and the ignorance of his guides, he found himself still four miles from the rebel stronghold at five on the following morning, he saw that the only chance of surprise was by a rapid advance of mounted troops. The General, accordingly, moved forward with a troop of Horse Artillery, a squadron of Lancers, and some of the Hyderabad Horse, and came upon the rebels as they were leisurely evacuating their position. The artillery opened on them, and the greater portion on the cavalry dashed into their ranks, committing much havoc, while the remainder intercepted their flight. The movement was completely successful. The General wrote: “Under fire of matchlocks and through jungle, which had been set on fire to impede our pursuit, but unavailingly, our troops came up with the rebels and the slaughter was heavy. To follow further without infantry (for the jungle was becoming dense) would have been as useless as imprudent, and the force returned to camp, leaving ninety-seven rebels dead on the field, and bringing with them thirty-seven prisoners.” Disspat, the rebel chief, long the terror of the district, who had just returned from Jhansi, narrowly escaped capture. His two nephews, equally notorious for their villainies, fell into our hands, and, with seven other prisoners, were hanged in the evening. Much baggage, cattle, grain, and matchlocks were found. The village and rebel stronghold was then completely destroyed by the field engineers.

On 16th April General Whitlock arrived at a place between Jheeghun and Banda, called Mahoba, and thence proceeded with all despatch to Banda, a course he had not only proposed to himself to adopt, but which Sir Robert Hamilton had urgently requested him, in a letter dated the 12th inst., to carry out, so that after the capture of the city, he might clear the right bank of the Jumna between it and Calpee, and be thus in a position to act in co-operation with the Central India force at Calpee. General Whitlock approached Banda on the 19th, and was met by the rebel forces, who, headed by the Nawab, came out to give him battle. A general action now ensued. The insurgents were estimated at 7,000 strong, of whom 1,000 were Sepoys of the Bengal army. The engagement last several hours, and, after a severe contest, terminated in the total defeat of the enemy, who left on the field more than 1,000 of their number, of whom 800 were killed, and several guns.

An officer thus describes the action of the 19th of April: “The engagement commenced a little before daybreak, and lasted till near noon – frightful work under such a sun. The enemy had taken up a strong position about five miles in front of Banda. Their guns were planted in a cluster of mango trees, not far from the village of Gourier; their infantry were posted in adjacent nullahs, while men concealed in the trees poured an incessant musketry fire. As soon as our advanced guard, about 600 strong, approached under Colonel Apthorp, the enemy’s batteries, which commanded the road, opened fire, but our men steadily advanced until within 400 yards of the enemy. Then, under cover of our guns, Colonel Apthorp, whose coolness, skill, and courage were beyond all praise, made a flank movement, which effectually turned their position. Our men were, however, severely galled by the heavy fire kept up upon them from the numerous enemies in the nullahs, and the trees around. Colonel Apthorp saw that, in spite of overwhelming odds, there was nothing for it but to charge. The 3rd Europeans proved themselves worthy of their leader, and though the enemy disputed the ground and crossed bayonets with our men, nothing could stand before the British bayonet, and, after a short struggle, they gave way. The cavalry, on their side, who had been ordered to charge and take the guns on the enemy’s left, did their work with no less heroism, and succeeded in capturing three guns.

“In the meantime, the enemy’s cavalry, supported by a portion of their infantry, had endeavoured to make a diversion by stealing round behind a village which had covered Apthorp’s advance, and making a détour over some elevated ground at the back of it, with the intention of attacking the main column in the flank or rear; but this movement was fortunately discovered, and Major Bryce’s battery of guns, which had already done good service with the advanced party, opened on them a well-directed fire. Brigadier Carpenter then ordered a party of skirmishers to take care of them, and a few vollies from the Enfield rifles soon sent them to the right-about, leaving their infantry in the ravines of the hill to be cut to pieces by our troops.

“After pursuing them about two miles, we halted to collect the force, and to give the men a little rest, which they sorely needed under such a frightful sun. About a mile beyond us was a small river, with a high bank on the further side, intersected by ravines. Here we found that the enemy were again making a stand; but this time Captain Palmer had come up with our big guns. The first shot, admirably directed, pitched right in amongst them, killing, as some say, their chief in command. After one or two repetitions of the dose, they found they could bear it no longer, and away they all went pell-mell towards Banda, much to our satisfaction, for the second position was even stronger than the first. After them, of course, we went; the Lancers and the Horse Artillery leading, and a beautiful sight it was to see them going ventre à terre over that difficult ground. Brigadier Miller and Major Oakes led the way, and Major Mayne, with the guns, was close behind. They overtook and captured another of the enemy’s cannon; but here Brigadier Miller was wounded, and but for the prompt rescue of Captain Clifton, of the Lancers, would have been killed. The pursuit was continued to the banks of the Kane, which is about one mile and a half from Banda. Here they made their first stand under the walls of a fort on the river’s bank. A further pursuit, it was apprehended, might bring us under the fire of the fort, and the ground near the river was of a most difficult nature. Hence, therefore, the recall was sounded, and the victors halted. We might, as it proved, have followed the enemy across the river, and even through the town of Banda, where the Nawab himself would have been captured. We are now masters of the place, and parties have gone out from camp to beat up the lurking-place of several of their chiefs.”

The Nawab fled from the field, it was believed, in the first instance to Kirwee, but, subsequently, he made in the direction of Calpee, and threw himself into that city with 3,000 men. The British troops took possession of Banda, and found in the palace a large amount of loot. The city was half deserted, while the military station was completely destroyed. The houses being burned down or levelled, and the gardens ruined. The church appeared to have been a special object of antipathy of the mutineers; not only had they made a target of the tower, which was pitted all over with cannon shot, but they had blown off the roof with gunpowder, torn out all the window-frames, and undermined the walls, evidently with the intention of blowing up the building, one corner of which had been much shattered. On the Sunday following the action, the chaplains of the force gave Christian burial, in a vault in the centre of the church, to the remains of the unfortunate people who had been murdered in the previous June, and whose bones were identified and collected. General Whitlock telegraphed his success to Lord Clyde and to Sir Hugh Rose, with both of whom he was acting in co-operation, and also to the Commander-in-Chief at Madras.

Sir Hugh having applied to Whitlock to co-operate with him in his advance on Calpee, the latter wrote to the Governor-General, asking for reinforcements from the north of the Jumna for his own column, in order that he might respond to the call, and waited at Banda for the reply. The Governor-General received the application on the 28th, and, at once, replied that no men could be spared to reinforce the Madras column, and that he had better remain at Banda, as the presence of a military force would be required there for some time. Almost on the same day, he received a memorandum from General Mansfield, Lord Clyde’s Chief of the Staff, directing him to march up the right bank of the Jumna, to assist Sir Hugh Rose in the reduction of Calpee, if the country in the vicinity of Banda and to the Eastward was sufficiently pacified. General Whitlock, considering that his presence at Banda was necessary in the unsettled state of the country, resolved to remain where he was; but his troops were nevertheless not idle, for, on the 18th April, he sent off a strong detachment, under Brigadier Carpenter, to escort the Rajah of Chirkaree to his capital, where the Rajah’s family were still in some danger. About this time sickness attacked the force, and continued with great intensity all the month of May.

In the meantime Sir Hugh Rose continued his victorious career. He stormed Koonch on the 7th May, and, at length, with only two weak brigades, performed the great achievement of carrying Calpee by storm on the 23rd May, after a desperate battle at Golowlee on the Jumna. Previously to this the Governor-General had, in reply to Sir Hugh’s repeated and earnest solicitations, directed General Whitlock to support him, if he could spare any portion of his troops, and stated that some reinforcements now on their way to Banda would reach him on the 26th. Upon receipt of these instructions, General Whitlock wrote to Sir Hugh a letter which the latter received on the 30th May, stating that he was expecting his second brigade, under Brigadier McDuff, immediately, and that he would then reinforce him with a brigade efficient in all arms. This second brigade arrived at Banda on the 27th May; but meantime, on the 23rd, Calpee had fallen. These particulars are necessary to show that the subject of this memoir was desirous, like a gallant soldier as he was, to assist his brother in arms; and that the fact of his not being able to co-operate in the feat of arms, which it was thought at the time had closed the campaign as far as the Central India force was concerned, was due in no measure to backwardness on his part.

Lord Clyde issued a general order on the 28th May, congratulating the three columns under the command of Generals Rose, Whitlock, and Roberts, upon the success of their labours, but, though well deserved, it was premature. On the fall of Calpee, Sir Hugh wrote to General Whitlock informing him that he did not require his assistance; and, in reply, the latter, after warmly congratulating him on his success, proceeded to say “I was to have marched this morning to join you, but now proceed to look after Narrain Rao, who has a large column of rebels and guns with him. My small column has suffered very severely. My aide-de-camp and myself were prostrated from the effects of a coup de soleil, and I am only now recovering. We have lost from sunstroke five officers and several men. It was frightful, the heat. Now we are all better. The rain has cooled the air considerably. I have just heard that some of the cavalry from Calpee are making their way to Narrain Rao, but I disbelieve the fact. I fancy the rebels look to the effect of the sun on our troops, but you have set them to rights on that point.”

This Narrain Rao, whom General Whitlock announced his intention of “looking after”, was the chief of Kirwee, a town about 50 miles from Banda. As early as the 22nd April, three days after the action at Banda, this prince had written to Major Ellis, political agent with General Whitlock, stating he was not in rebellion, and was prepared, if allowed an opportunity, to prove his loyalty. In reply Major Ellis wrote back on the 27th, directing him to appear before him at Banda, bringing with him his colleague, Madho Rao, and Radho Gobind, his prime minister, and to come without guns, and attended by not more than 100 followers. Narrain Rao wrote back in reply on the 29th, saying that he was discharging his men as fast as possible, but would come in at the end of a week or ten days. Shortly after this, orders were received from the Supreme Government for the arrest of these princes, and General Whitlock set out for Kirwee, on the 2nd June. When he was some ten miles from the city, on the morning of the 5th, Narrain Rao and Madho Rao, descendants of the once mighty Peishwa of Poona, came into the camp, and surrendered themselves; their prime minister, Radho Gobind, having, at the approach of the British force, retreated to a fort sixteen miles distant from Kirwee, called Manickpore, from which he fled on the 7th, when threatened with an attack.

On the following day, the 6th June, General Whitlock entered Kirwee, without meeting with any opposition, and took possession of the palace. In the court-yard he found thirty-eight new brass guns, and every description of munitions of war, including 800 muskets and belts; also jackets and accoutrements of the 50th and 67th regiments of Bengal Native Infantry, and of the Gwalior Contingent, the Sepoys of which corps had fought against us at Chirkaree, Betwa, Koonch, and Calpee, all forming incontrovertible evidence that Tantia Topee, who had commanded the rebel troops, had been befriended by Narrain Rao. In the palace also was found the chief part of the booty, consisting of forty-two lacs of rupees in coin, with a vast quantity of specie, jewels, and diamonds, the distribution of which gave rise to that cause célèbre of admiralty prize suits, the great Banda and Kirwee case. Meanwhile, on the very day that General Whitlock had captured Kirwee, Sir Hugh Rose set out from Calpee for Gwalior, in consequence of the receipt of news that the rebels had rallied under their old leaders, the Ranee of Jhansi, the Nawab of Banda, Rao Sahib, and the notorious Tantia Topee, and, having compelled Scindia to fly to Agra, had entered Gwalior, and proclaimed Nana Sahib Peishwa. Sir Hugh Rose, having received reinforcements on his march, defeated the rebels in a general action on the 19th, when the Ranee of Jhansi was killed, Tantia Topee and the Nawab of Banda escaped only by a precipitate flight, Gwalior was recovered, and the Maharajah reinstated on his throne.

The general order of the Supreme Government, published to the armies of the three Presidencies on the 9th June, after enumerating the part played by the army of Bengal in the successful conduct of the plan designed by the military authorities, proceeds to say, “The three columns put in movement from Madras and Bombay have rendered like great and efficient services in their long and difficult marches to the Jumna, through Central India, and in Rajpootana. These columns, under the command of Major-Generals Sir Hugh Rose, K.C.B., Whitlock, and Roberts, having admirably performed their share in the general combination arranged under the orders of his lordship the Governor-General. The combination was spread over a surface ranging from the boundaries of Bombay and Madras to the extreme north-west of India.” Again, after the fall of Gwalior and capture of Kirwee, another general order was issued, dated Calcutta, 22nd June, 1858. The Commander-in-Chief, after congratulating Sir Hugh Rose on his successful operations throughout the campaign, and at Gwalior, proceeds to point out in how great a measure the successful accomplishment of these victories, was due to the less showy successes of the Nerbudda and Rajpootana field forces. Sir Colin Cambell said: “It must not be forgotten that the advance of the Central India field force, formed part of a large combination, and was made possible by the movement of Major-General Roberts, of the Bombay Army, into Rajpootana on the one side, and of Major-General Whitlock, of the Madras Army, on the other; and by the support they respectively gave to Major-General Sir Hugh Rose, as he moved onwards in obedience to his instructions. The two Major-Generals have well sustained the honour of their Presidencies. The siege of Kotah and the action of Banda take rank amongst the best achievements of the war. The Commander-in-Chief offers his best thanks to Major-General Roberts, to Major-General Whitlock, and the various corps under their command. He is happy in welcoming them to the Presidency of Bengal.”

A donation of six months’ batta was given to each of the three columns, that for the Nerbudda field force being awarded on the 13th November, and, on the 7th April, 1859, Her Majesty announced that a clasp for “Central India” should be granted to the troops which, under the command of Major-General Whitlock, performed such important service in that portion of her dominions – the armies of Sir Hugh Rose and General Roberts being, of course, awarded a similar decoration. After the fall of Kirwee, General Whitlock was appointed, on the 7th July, to a divisional command, embracing the Saugor district. Operations were undertaken, in August, by detachments, under Brigadiers Carpenter and McDuff, but, owing to the incessant rain which completely flooded the country, they were carried on with the greatest difficulty, though in every instance with success. Again, in December, General Whitlock took the field against some rebels who were ravaging the country, and his troops were engaged in a small affair, and stormed the heights of Punwarree, not far from Kirwee, which city having been previously abandoned, was recaptured at the same time. On this occasion a further small amount of treasure was discovered, and dug up in the fort. Thus propitiously for his honour, and also be it said for his purse, closed the war services of General Whitlock and the Nerbudda field force.

According to the 43rd Foot’s Regimental History: “The march through Central India was one of the most arduous undertaken by any troops. Part of the field force marched no less than 1,300 miles, with only an occasional halt at large stations for a few days for the purpose of laying in commissariat stores. Some idea may be formed of the excessive exertion and fatigue undergone both by officers and men, when it is considered that this march was, in most part, performed during the hottest season of the year, in which the mean temperatures exceeded that of any known during the fifteen years preceding. The marches commenced before daylight, usually as early as two a.m., and it frequently happened that the rear of the column did not arrive in camp until four or five p.m. A mere country track constituted the only route, at times crossing chains of high, precipitous hills, cutting through rocks and jungles for days together, traversing and passing numerous rivers, many of great breadth, without bridges or boats. Now and again the troops were employed in dragging the carts, some hundreds in number, containing ammunition and stores, over almost insurmountable obstacles where cattle were nearly useless. The monsoon, usually commencing in June, did not in this year visit Central India until the middle of July, consequently the acute sufferings of the troops under the burning and arid breezes of that inhospitable region, were not only most exceptionally intense, but protracted. The 43rd Regiment alone lost three officers and forty-four men from sunstroke.”

Besides receiving the thanks of the Governor-General, and of Lord Clyde in an autograph letter, General Whitlock was mentioned in the vote of thanks awarded by both House of the Imperial Parliament to officers in command of divisions, and to the troops employed in the suppression of the mutiny. He was created a K.C.B. in 1859, and, on the 30th September, 1862, received the colonelcy of the 108th Regiment, the corps which he had raised and commanded as the 3rd Madras Europeans. Sir George Whitlock commanded the northern division of the Madras army during 1860-61, but the state of his health compelled him to resign the command and return to England. On April 9th, 1864, he became a lieutenant-general.

It would appear that nothing could be simpler than distributing booty earned by troops in the field, yet this, though a common-sense view, is not a correct one. The “law’s delays” are proverbial, and so ought to be the dilatoriness of the authorities in awarding prize captured in war. The delay in this instance partly arose from claims to share by officers and troops other than those serving under General Whitlock. This gave rise to a famous lawsuit, in which the whole learning of the bar was arrayed, the papers and documents filling many folio volumes. On the 30th June, 1866, the Right Hon. Dr. Lushington delivered judgement in this celebrated case in the Court of Admiralty. The judgement, which was printed in Blue-book form, took three hours in the delivery. In the course of this elaborate exposition, the venerable judge stated that the value of the booty captured by Sir Hugh Rose at Jhansi, Calpee, and Gwalior, amounted to £49,000; that taken at Banda and Kirwee by Sir George Whitlock’s force was valued at £700,000; while the third column, the Rajpootana filed force, under Sir H. Roberts, became the captors of prize of the estimated value of £18,200. For the distribution of this property it had been proposed that the whole proceeds should be thrown into a common fund, and be divided equally among the forces under the command of the three gallant generals named above, but the prize agents of Sir G. Whitlock’s force had preferred a claim that the property captured at Banda and Kirwee should be granted exclusively to that force. Claims to participate were preferred by the executors of the late Lord Clyde, as Commander-in-chief, on behalf of himself and his personal staff; by Sir Hugh Rose, on the ground of his force having co-operated in the actions or movements of the troops which led to the capture; also by Generals Smith and Roberts, Colonel Middleton, Major Osborne, Political Agent at Rewah, Colonel Hinde, in command of the Rewah levies, Colonel Keatinge, and others.

The great principle which is recognised as the basis of the prize law is, that all booty taken in war belongs absolutely to the Crown, but for more than a century and a half the Crown has granted the prize to the captors. The claims of all the above officers – as also of General Wheeler, in command of the Saugor district and garrison, of General Carthew and the Futtehpore moveable column, of General Maxwell in command of another column operating on the Doab – were disallowed, with the exception of Lord Clyde and staff, and that of Colonel Keatinge and the 50th Regiment, for the reason that, although the corps was at Saugor till after the capture of Kirwee, yet while there it was, as it had been at Jubbulpore, encamped and equipped in readiness for any immediate march that might be ordered by General Whitlock, and formed, therefore, part of his division.

On the 28th March, 1867, nine years after its capture, the long-expected order for the payment of the first instalment of the booty, was issued by the Governor-General, as follows: “The Banda and Kirwee prize money is payable to the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Clyde, and Head Quarters’ Staff, who were in the field between the 19th April and 6th June, 1858, and to the troops of the Saugor and Nerbudda field force who were under the immediate orders of Major-General Sir G.C. Whitlock, K.C.B., between those dates.” The troops entitled to share were two troops of Madras Horse Artillery, one company of Royal, and three of Madras, Foot Artillery; one company of Madras Sappers, a wing of the 12th Lancers, and a detachment from the 2nd Cavalry of the Hyderabad Contingent; Her Majesty’s 43rd, and the 3rd Madras Europeans; and the 1st, 19th, and 50th Regiments of Madras Native Infantry.

It may be mentioned that the costs of this long-protracted suit up to the date of this order, were no less than £60,000. The share of Lord Clyde, as Commander-in-Chief, was also about the same sum, while that of Sir G. Whitlock, the actual captor, was not more than £12,000. Early in 1868, a Prize Committee, appointed by the officers of the Nerbudda field force, set to work in earnest to ascertain the value of the spoil acquired at the capture of Kirwee; and not a whit too soon, for the Government of India had attempted to subtract £52,325 from the prize fund, in order to cover a deficiency to that amount of land revenue, said to have been plundered by rebels in the Banda district. But the Secretary of State, Sir Stafford Northcote, took counsel with the law officers of the Crown on this question, and set aside this unjustifiable act of the authorities at Calcutta, who, however, appropriated no less than £256,000, a sum which represented the debt due to the ex-chiefs of Kirwee by the East India Company and by private debtors. The Prize Committee submitted their claim for this property to some eminent jurists, and received a favourable opinion, signed by five counsel of high legal attainments; but the Government resisted the claimants, and doubtless much is to be said against the captors’ contention. But the wranglings of lawyers soon ceased personally to affect the general who led the forces that captured this valuable prize, for Sir George Whitlock had reached that “bourne whence no traveller returns”.

On his return from India, he resided, up to the date of his death, at Exmouth, in his native county of Devonshire. He remained in tolerable health till the commencement of the winter of 1867, when he was attacked with paralysis, and, after much suffering, expired on the 30th January, 1868, leaving a widow, with three daughter and two sons, to mourn his loss.

The subject of this memoir was a brave soldier and an honourable man; and though he cannot be regarded as taking high rank as a soldier, the name of Sir George Whitlock may not unworthily be placed among those of India’s distinguished generals.