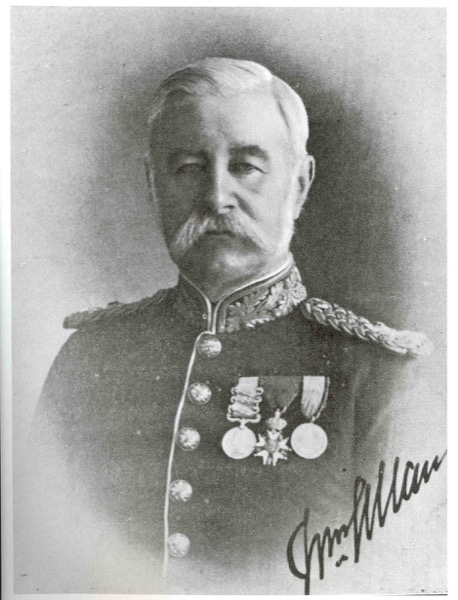

My Early Soldering Days by Major-General William Allan

Preface

I have often been asked by friends and others to collect my husband’s letters written to his mother during his early soldiering days, including the Crimean Campaign; but in consequence of his objection to having what he calls “his old rubbish” put into print, I have only recently, and with difficulty, gained his consent.

Naturally, a General Officer looks upon his effusions written when a Subaltern as “rubbish,” so I would ask any one who is good enough to read the following extracts to recollect that they are taken from letters written unreservedly to his parents, and that at the date of their commencement he was only just emerging from boyhood, although he was soon to learn what war with all its stern realities meant. I would also beg any readers to bear in mind under what trying difficulties some of the letters were penned, though he seldom, if ever, allowed a week to pass without sending a letter home. Being mercifully preserved throughout the Campaign, he was able to do more trench work than most others, so I cannot but think that these notes – showing many minor details of his daily life during that eventful period – may prove interesting to others besides his immediate family circle.

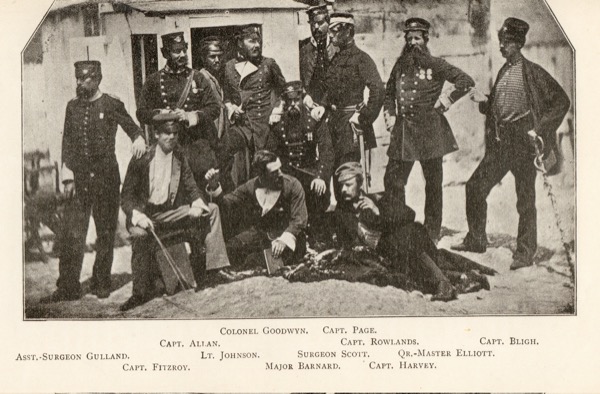

Most of the Illustrations in the book are from photographs taken at the time of the War, and they are now reproduced for the first time; others we obtained when visiting the Crimea again in 1892. It is not easy to describe with what intense interest I went over the old sites and battlefields with my husband, and how glad I am I have had the pleasure of this most interesting and delightful trip before Russian restrictions precluded foreigners from so easily visiting Sebastopol.

J. H. ALLAN.

I began my military career when gazetted to the 41st, the Welch Regiment, on the 12th July 1850, at the age of eighteen, and joined at Cork on the 1st September. The regiment embarked the following February for the Ionian Islands, and was stationed for two years at Zante, when it was ordered to Malta. On the departure of the Service Companies, I, being one of the junior ensigns, was left with the Depôt, and quartered at Westport, Castlebar, Ballinrobe, and Boyle.

In June 1853, I left Southampton for foreign service, in the P. & O. S.S. Ripon, and landed with my brother ensigns, Swaby and Harriott, at Malta, on the 30th June, after an eventful incident during the voyage, which might have cut short my soldiering on my twenty-first birthday. On the night of the 22nd, having come through the Bay of Biscay, it was reported that we had passed a small boat, on which the officer of the watch, thinking it might be from some wrecked vessel, enquired of the captain if we should stop and hail her, but he received an answer in the negative. Soon after, a second boat came in sight, which caused suspicion that we were too near the coast of Spain. We were carrying sail, and going 11 knots. At 11 P.M., we ensigns, with four others of the 49th, Earle, Corbett, Armstrong, and Corban, had just retired to our cabins, when we suddenly heard a shout from the look-out man, “Breakers ahead!” followed immediately by the ship’s orders, “Down all sail,” “Stop her,” “Back her.” It was a dark and hazy night, but, fortunately for us, the moon appeared from beneath the clouds in time to show the danger into which we were running; a few minutes more and we must have been wrecked. Great excitement and consternation prevailed on board, as, when the vessel was stopped, we could see the breakers in front of us, and a large rock on our starboard quarter. Owing to the thick, foggy weather down Channel, and across the Bay, the ship’s officers had failed in taking sights, and it was found the strong current had drifted us 15 miles out of our course. The boats we had seen were fishing-boats. We took some of the men on board to help us out of our difficulty, and put us on our right course again. We had to back out from the shoal of rocks the same way as we had entered, and all felt thankful to have escaped what might have been a great catastrophe.

Fort Ricasoli, Malta, 18th July 1853

I cannot say my first impressions of Malta are very prepossessing; it may be a pleasant place in winter, but at present it is far too hot to be agreeable; with the thermometer standing at 80° at night. The heat at first quite knocked me up, but I am now getting used to it.

It is delightful boating, with a setting sun and a cloudless sky. One is not inclined to walk far in this climate, so rowing is the best exercise one can take. When it gets cooler, I shall hire a horse now and then, and explore the Island. It looks very desolate at present, as there is no grass, and the crops were reaped in May; added to which, the smell of garlic and the ugly women disgust one.

A fine new steamer arrived here yesterday from Southampton, called the Vedetta. She is to ply between Malta and Marseilles. She can go 17 knots an hour, and is built for speed to run the French packets off the line. This is a curious place; though on the direct line from India and Constantinople, we never hear any news except through England.

The Ripon had no deck cabins except the captain’s. Ours was in the front part of the vessel below the first deck. These vessels carry no steerage passengers. We passed too far from Algiers to have a good view of it.

One of the entrances to Valetta is by the Nix Mangiare Steps (i.e. “nothing to eat”), which gets its name from the number of beggars that are congregated there. From Fort Ricasoli, where I am quartered, to the town, is about a quarter of an hour’s row. The nearest route is across the Grand Harbour, where most of the shipping lies, and the fleet also.

To-morrow evening some of the few remaining English have been asked to the Officers’ Mess, to a sort of cold collation. I am sorry I cannot be one of the party, as I dine with the General at St Antonio. I should have liked to have made the acquaintance of some people; as yet, I do not, know any. There are very few I am told at present in Malta worth knowing. I may meet some ladies at the General’s, if it is not a gentlemen’s party.

There were great illuminations in the town the other evening in honour of the Virgin Mary, and several processions the next day; two military bands played in front of the palace from nine till midnight.

The strawberries here are now all over. When I first came I had a large plateful every morning at breakfast of the Alpine kind.

Swaby, Harriott, and I are going up for our examination at Fort Manoel on Wednesday. I drilled a company this morning, and found I got on swimmingly, but the sun is dreadfully hot even at 6 A.M.

20th July.

Last evening I dined at St Antonio. The General is a very nice old fellow. There is no humbug or formality about him, and he received me in such a kind friendly manner. I had a long chat with him. He says he is going to write to father, and he asked me to drop in some day at 2 P.M. and take a family dinner; or any evening I was riding out in their direction, to come in and have tea and refreshment. We had a very pleasant party at dinner, eighteen in number, no ladies, and almost all redcoats. After dinner we adjourned to the drawing-room, where we met Mrs Jarvis, Miss Jenkins, and Miss Younger. After a cup of tea, we all went out on to the verandah, and enjoyed iced drinks, cigars, etc. What a luxury ice is in this climate!

Returning home in the evening, we had a chapter of accidents; I think the drivers had been indulging too freely at the General’s expense. Bush and I were in a carriage together. Shortly after starting, our driver let the reins get under the tail of one of the horses, which made it jib, and nearly sent us against the wall. We had not proceeded much further when the horse kicked over the pole and fell, so we cleared out and got into one of the other conveyances, and after going about a mile, we came upon a carriage lying at the road-side, broken to pieces. The coachman had run into another vehicle, and was thrown off the box, had his arm fractured and head cut. Strickland, of the Commissariat, had his head severely bruised, and two others were more or less hurt. We removed the unfortunate driver into one of the carriages, and drove him to the hospital. I don’t think that he is dangerously hurt. There is little doubt that by this time it is reported in the garrison that we were all drunk, having had so many mishaps. We came home at a racing pace; the drivers must all have been a little “lushey.”

30th July.

For more than a week I have been a good deal engaged attending a General Court-Martial. The paymaster of the —th regiment is being tried for making away with public money entrusted to his care; and what with writing, exercises, and studying for my Italian master, my time has been very much taken up. This hot weather is not at all conducive to work. I have now been here exactly a month. The impression I have formed of Malta is not a very delightful one; the thermometer is 87° by day, and 83° at night. I am not yet home-sick, although I fancy there are very few places like “Merrie Old England.”

The Indus is in sight; we expect Captain Bourne by her; he exchanged with Bagot. I am also in hopes that I may hear something of my lieutenancy, as I think Bertram will have to sell, or even if he is allowed to join the Depôt, the change would send Johnston out here, which I do not think would suit the old boy with his family.

Ten days ago, Handcock, Fitzroy, and I were out sailing in the evening; it was blowing pretty fresh, and the sea was high. We went a short distance, then took a tack round by the Quarantine Harbour to Fort Manoel, where the headquarters of the regiment is stationed. On our return home we noticed a boat in our wake. It was by that time becoming dark, and as we were passing Fort St Elmo, a squall caught us, and if Handcock had not let go the sheet, we should have capsized. Hearing a shout, we looked round, and found the sail we had previously seen had disappeared, so we immediately took down our canvas and put about, but the shutters (where the oars are placed) had got so swollen with the wet, that it took us some time to get the oars out. It was nearly a quarter of an hour before we reached the boat, which was keel uppermost In a minute or two we were much relieved by a Maltese boat coming up alongside of us, with a soldier in it (Private Anderson, of our regiment). He called out that it was Mr Bligh’s boat that was upset, and that he had been sailing with him, but Bligh is a first-rate swimmer, and had succeeded in reaching St Elmo point. It was almost a miracle that he was not dashed to pieces against the rocks, there was such a heavy sea. The soldier, who is not a great hand at swimming, was nearly exhausted when he was picked up by the native boatmen. Bligh did not know much about sailing, but he saw us going out, and thought there was no reason why he should not follow. Handcock is an experienced hand, otherwise he would not have found me in his boat that night. It has taught us all a lesson to be more careful in future. I must now go out in my boat and, get some rowing exercise. I have not got a sail for her yet, but propose going round to-night to the other harbour to see about it.

1st August.

I intended to have despatched this by the Indus, but will now post it to-morrow via Marseilles, and trust that it may not be over a quarter of an ounce; if it is, it must wait for the Southampton, as I do not think it is worth 2s. 9d. I met the General when riding the other evening. I intend going out to St Antonio on Thursday with Bush, and stopping to tea, if they are at home.

Captain Bourne arrived by the Indus; we hope to get a step out of him shortly, by showing him the “dust” (money) that the 17th could not produce. He offered to sell for £700 over regulation, but they could not make it up; Bagot gave him £250, and a free passage to exchange. He will easily get the £700 in this regiment, if he is still anxious to go, and I sincerely trust he may be, as I do not know where to look for my lieutenancy, if he does not sell. Bertram is in for a long spell of sick-leave.

The General Court-Martial wound up its proceedings on Saturday. There is no doubt E— will be cashiered, and it will be fortunate for him if he only receives two years and not transportation. We shall not know the sentence till it has been laid before Her Majesty.

The captain of the Ripon, on returning to Southampton, ran down a coal barge, and, I hear, is likely to be suspended for six months. I have not seen anything of the Governor. He does not entertain much at this season, as he lives in the country.

I returned yesterday from my travels (having spent a very pleasant month in Italy), exceedingly delighted with all I have seen. My only regret was having so short a time to see the numerous works of art. However, I visited all the principal sights and ruins, and came back in a French packet, after a boisterous voyage. The Museum at Florence is most interesting; there is a wonderful collection of waxworks there, consisting of wax flowers; the gradual development of the human frame from a skeleton, dissected and put together again, so, that a person, totally unacquainted with anatomy, can easily follow its entire construction; an egg from the day it is laid until the day the chick comes forth; the different stages a moth goes through, several species of fish, and innumerable other animals, all beautifully executed. But there was nothing I was so much struck with, as the wonderful models of the human frame.

The Cathedral at Florence is very beautiful, but before leaving Italy, I was heartily sick of seeing churches. Santa Croce is the finest in Florence. There are so many galleries, with lovely paintings and sculpture to visit and study, that one could well spend a couple of months in Florence. I regretted much that I only had a week to spare there.

The Austrians are hated throughout Tuscany, and the King is in very bad odour; he is at present residing at Pisa. The Tuscans have to pay for the occupation of the Austrian troops. I went by rail through a fertile country from Florence to Siena. The Cathedral is well worth a visit; the marble pavement is of Florentine mosaic, and very rich. The road from Siena to Borne is uninteresting, and surrounded by low volcanic hills; the journey takes thirty-six hours. I remained at Rome ten days, and made the most of my time, seeing all the principal objects. What wonders still remain of ancient Rome! They certainly made monuments and masonry in those days to stand. I had no idea the baths of the Emperors covered such a large area, or that they were on such an extensive scale. I am sorry I devoted too much time to the private palaces and churches, as I had not sufficient left to see the Vatican properly, although I was there a whole day and part of another; it is only open to the public on Mondays, but a tip will unclose many a bolt. To see the Palace thoroughly would take a month at least. I believe in Rome one could see something new every day in the year, but the town itself is miserable, and looks dull. It is not a city where I should care to reside long after having seen the sights.

I inspected St Peter’s minutely. What an amount of money has been expended on it; 47,000,000 dollars up to 1694. Everything possible has been done in the way of embellishing it, and it is certainly a most splendid edifice. I went up to the ball which can contain sixteen persons. The ascent is easy. A broad winding slope leads nearly to the top, the remainder is by steps. From the upper gallery, there is a fine view of the city and the surrounding country, which is interspersed with grand old remains of palaces, baths, and aqueducts. The best view of the ruins is from the top of the Capitol. Looking down, from there, you have a fine idea of their extent and grandeur. It is a pity to see so many beautiful private palaces going to wreck throughout Italy. Very few of the proprietors, though called Princes, can afford to keep them up; gradually, one by one, they are being sold, and magnificent collections of pictures and sculpture broken up and dispersed. Among the Government galleries there is a deal of rubbish, which is kept because the works are ancient.

The day after my arrival in Rome, Ambrose and Birmingham of the Buffs, with whom I parted at Naples, arrived, and during my stay I worked hard. It was much pleasanter for me going about with them than being alone. After St Peter’s, the finest churches are St John Lateran and St Maria Maggiore. The former is the oldest in Rome, and founded by Constantine. Both the interior and exterior are very grand. In the centre nave are colossal statues of the Apostles. The Chapel of the Corsini family is most magnificent, and decorated by the extensive scale. I am sorry I devoted too much time to the private palaces and churches, as I had not sufficient left to see the Vatican properly, although I was there a whole day and part of another; it is only open to the public on Mondays, but a tip will unclose many a bolt. To see the Palace thoroughly would take a month at least. I believe in Rome one could see something new every day in the year, but the town itself is miserable, and looks dull. It is not a city where I should care to reside long after having seen the sights.

I inspected St Peter’s minutely. What an amount of money has been expended on it; 47,000,000 dollars up to 1694. Everything possible has been done in the way of embellishing it, and it is certainly a most splendid edifice. I went up to the ball which can contain sixteen persons. The ascent is easy. A broad winding slope leads nearly to the top, the remainder is by steps. From the upper gallery, there is a fine view of the city and the surrounding country, which is interspersed with grand old remains of palaces, baths, and aqueducts. The best view of the ruins is from the top of the Capitol. Looking down, from there, you have a fine idea of their extent and grandeur. It is a pity to see so many beautiful private palaces going to wreck throughout Italy. Very few of the proprietors, though called Princes, can afford to keep them up; gradually, one by one, they are being sold, and magnificent collections of pictures and sculpture broken up and dispersed. Among the Government galleries there is a deal of rubbish, which is kept because the works are ancient.

The day after my arrival in Rome, Ambrose and Birmingham of the Buffs, with whom I parted at Naples, arrived, and during my stay I worked hard. It was much pleasanter for me going about with them than being alone. After St Peter’s, the finest churches are St John Lateran, and St Maria Maggiore. The former is the oldest in Rome, and founded by Constantine. Both the interior and exterior are very grand. In the centre nave are colossal statues of the Apostles. The Chapel of the Corsini family is most magnificent, and decorated by the first painters and sculptors of the age. In the family vault is a group (by Bernini) of Christ, supported by His Mother; it is beautifully cut, and I think equals anything I saw of Michel Angelos. On Sunday I heard the Pope officiate (Pope Pius IX). His Holiness is a fine-looking old man, but I cannot say much for the cardinals; they are not intelligent looking, and by their appearance one would judge that they were fond of good living. The Pope always dines by himself at the Quirinal Palace (his summer residence). I was shown through his private apartments; they are handsome, but plain. The Chapel adjoining is decorated by Guido.

The journey from Rome to Naples by diligence takes twenty-eight hours. From Capua, there is rail to Naples, and I was glad to avail myself of it, having had quite enough carriage work, which is slow and tedious. The distance by road from Capua is 16 miles, and the diligence takes four and a half hours to do it over, a frightfully bad road. On the journey, the annoyance one meets with from the inspection of passports and baggage is dreadful; it is much worse in the Neapolitan territories than in the others. Five times after crossing the Roman frontier, passports were demanded, and for signing them money is always expected; the system must be a goodly source of revenue to the Governments. On my passport I had more than twenty vises, which cost altogether 45s.

The road from Rome is picturesque, and of historical interest. Before reaching Terracino (the frontier station), you pass through the Pontine Marshes, which are more than 30 miles long, over a very dreary and desolate waste, with no habitations, barring a few post stations. The inhabitants are a sickly-looking people. After leaving Terracino, the country becomes very wild and rugged, and in olden times, was much infested with banditti, who took refuge in the mountains. A small place, “Itri,” Murray mentions as the birthplace of the celebrated brigand, “Fra Diavolo,” whom the English employed and paid to harass the French towards the end of the last century. Further on, we passed the tomb of Cicero and Gaeta, where the Pope took refuge when he fled from Home.

A curious incident occurred during my tour! I met Eccles, a late brother ensign, who had left the service, he had been travelling the night before through the Pass of Terracino, when the coach was stopped by bandits, and he and the passengers were robbed of all their valuables. He told me he had lost his watch and about £20, and he was then on his way to consult with the English Consul as to the best means of obtaining the wherewithal to continue his journey.

When at Naples, I visited the Museum, which contains most of the antiquities that have been excavated from the noted cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. It is very interesting to examine all the different things that have been brought to light, after being buried nearly 2000 years. Several of the cooking utensils are the same as we use at the present day. Many fine works of marble and bronze have been dug up. How extraordinary it is to see the colour of some of the frescoes, which are nearly as fresh as the day they were painted. The Museum contains many other very fine relics collected from various quarters, besides the things found at Pompeii. The celebrated “Toro Farnese” is there. To view the rooms is quite in character with everything else the traveller sees in the Neapolitan territories. Money, money, is the cry; every separate room is under the lock and key of a different custodian, who are all appointed by Government, and those people have to give a fixed sum every year to the Treasury. What with passports, examination of baggage, and money extorted for sight-seeing, a good round sum must be added to the revenue.

I was much pleased with Pompeii and Herculaneum. There is not much to be seen at the latter beyond the excavation of the theatre, which, along with the town, was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius, and every part filled up by the running lava, which is as hard as stone, so is nothing less than a theatre underground, cut out of the solid rock, the lava having been removed from the interior.

The town of Resina is built on the top of the ancient city of Herculaneum, so when underneath you hear the carriages rolling in the street above you. Pompeii is a great deal more interesting, but nearly everything worth preserving having been taken away to the Museum in Naples, little remains except the walls, and even these are stripped, when a good fresco is discovered. Although the roofs of the houses have fallen in, the side walls remain, and are still very perfect. The rooms are small, and built all much after the same style. The streets are very narrow, with paved footpaths on the sides. The floors of the rooms are mosaic; the finest and most perfect have been removed to the Museum. In the centre of almost all the houses there is a small open court.

Shortly before the eruption, an earthquake threw down many of the public edifices. The appearance of the ruins betokens a city of wealth and grandeur.

There are several temples and two forums. As yet no houses have been discovered which could have been inhabited by the poorer classes. The ground floors were usually shops. The excavations have been going on – off and on – for 100 years, but so slowly that, as yet, only a quarter of the town is uncovered. I believe in future they intend to leave some of the houses as they find them, which will add to the interest of the place.

The weather, when I was at Naples, was wet and hazy, which prevented my making some of the excursions I wished; but the day before I left was lovely, so, with a party of eight, I went to Vesuvius. We drove to Resina, and from there took ponies to the cone of the hill, which is a steep but easy ride. We then dismounted, and began the climb on foot; the first part was the most trying, as it was over very fine ashes, in which one sinks ankle deep, but the upper part is lava, so it is easy enough. There are plenty of guides, who offer to pull you up or carry you in a wicker chair, but I declined all assistance. From the top we had a beautiful view of the Bay and the surrounding country, and we were fortunate in having such a clear day. At present, there is nothing issuing from the crater except sulphureous vapour, and yet the ground is so hot that an egg will boil in the crevices from which the smoke rises. We did not take long to come down the mountain, as the descent is very easy.

I made an excursion to Baie; the view is magnificent on every side. There are many places of interest en route, which have stood since the clays of the Cæsars – ancient temples, baths, and innumerable other ruins. I was surprised to find Naples so large a town; the beggars are swarming, and the filth in the streets shocking, but it is certainly beautifully situated, and must be a delightful winter climate.

No officers are at present allowed leave for England, and we do not know whether we are to go to the West Indies or not. I hope Greece or Constantinople may be our destination. The steamer Tritons now towing in quite a fleet of men-of-war, Prussian, Dutch, and the Agamemnon, five in all. They say that the contractor has an intimation to have supplies ready for 5000 more troops, along with a large number of Artillery, but it does not do to credit all the reports.

The last news from the East is that there has been a naval engagement (the Battle of Sinope) and that the Turks have got the worst of it. If so, it appears disgraceful that the combined fleet should be on the spot, and not help the Turks; the French I have met say, “It is England that has prevented them.” I would like to see Aberdeen sent to the right-about, and Palmerston in office, and then we would soon be at it.

The French seem to be trying to get up a row with Naples. The King of Naples has established quarantine on all French vessels, on the plea of cholera, but the truth is, he wishes to throw impediments in the way of the French, English, and Americans entering the country, for they are the only people who speak their minds freely. I could not land at Messina on account of quarantine restrictions.

Johnston has been recommended for the Regimental Adjutancy, but he says he will not take it if it is to interfere with his getting his promised appointment. It is a shame not giving it to some of the younger hands who have applied; Swaby and Rowlands both asked for it, still it is better for the regiment that Johnston should have it for a time to rub the men up. Bertram is talking of selling out and going to New Zealand; if so, and when Balguay is promoted by Tuckey leaving, the Depôt Adjutancy will be vacant, for which I intend applying, as I think I may have a chance, and if I get it, I shall escape at least two years of the West Indies. What do you think of the plan? Pratt and Skipwith are on leave and join the Depôt.

Officers’ Guard-Room,

25th December 1853.

I quite forgot, when sending off my last, that it was so near the close of the year, and to wish you all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. This day I have had the pleasure of spending on guard, so I cannot say that I have had a very enjoyable Christmas, especially as I had to dine all alone; the officers having agreed that they were all to feed together, none of them could favour me with their company. However, the day has not hung heavy on my hands, as I have had a number of visitors dropping in. You must know that a guard-room is very like a halfway house, which no person can pass without stopping at, so I have had no lack of society. After tattoo, the guard is closed to all visitors, as a precaution against the officer becoming incompetent to perform his duties, which now and then occurred when the —th was here, and open house kept all night.

This day’s mail from Marseilles brought private information that ships have been taken up to convey several regiments to the Mediterranean, so we may look forward to being under sail for the West Indies in about six weeks. The ships mentioned are the Canterbury and Georgiana. The passage to Jamaica will not be so pleasant in a freight ship as it was coming here in the Ripon.

Yesterday I was lunching at the General’s, no one there besides myself. The Army at large has met with a blessing in the resignation of Sir George Brown as Adjutant-General; he has always been averse to anything new, and is very unpopular. There has evidently been a quarrel at the Horse Guards. General Wetherall, the Assistant Adjutant-General has also retired; he was much liked, and will be greatly regretted. I suppose he did not feel grateful for General Cathcart being put over his head. Johnston has lost his interest by the retirement of Brown; he will probably now, poor fellow, not get an appointment. My hopes, with respect to the Depôt Adjutancy, I am afraid, are not likely to be realised, as Johnston told me it was already promised.

Next week we are to have a sham fight. The 41st and 47th are to attack Valetta on the Floriana side, which will be defended by the 49th and 68th. I am not yet acquainted with the entire outline of the engagement; the former succeed in forcing the outer works and beating the defenders back over Floriana to the Porta Reale, then a strong fire opens on us from behind the inner breastworks, and the fortune of the day is changed. It would puzzle a real enemy to establish a footing against such formidable batteries.

The thermometer to-day is 60°, and it is quite cold; in England it would be a hot summer’s day. I do not understand how one feels the cold here so much. Some of the, officers have fires all day; mine is only lighted in the evening, when I find it very comfortable. Handcock, Harriott, Lawes, and I, with two of the Artillery, rode out last night to hear Midnight Mass at Citta Vecchia. The opera singers being there, the music and singing were very good, and we enjoyed it. The Cathedral looked beautiful with so much silver displayed.

Nevertheless, I do not think it compensated us for the wetting we got riding back, as we were caught in several heavy hailstorms, although we only took a little more than thirty minutes to return, which was sharp work, considering the town is about 7 miles from this. I shall now turn into bed, which I suppose is not quite the thing to do when on guard, but there is no use losing a good night’s rest when it can be avoided.

The Colombo, a new screw, has made the fastest passage on record from Southampton, viz. seven days and fourteen hours, with six hours’ stoppage at Gibraltar. We expect Hunt to be sent home to the Depôt as paymaster instead of Wethered.

GUARD-HOUSE, MALTA

5th February 1854.

On the 29th I got my mother’s letter of the 23rd, which never failing epistle I look forward to every fortnight with great pleasure. I am on guard to-day. It has been one of great excitement, owing to the arrival of three mails – one from Constantinople and two from Marseilles. The Caradox, a despatch boat, was one. She only remained three hours, and then left for Constantinople; she has on board a French Colonel of Engineers, and General Burgoyne, Inspector of Fortifications. They were on shore for a short time, and took a look at the fortifications of Valetta, and also inspected the 41st in heavy marching order, and afterwards, with the Governor and the Staff, went round the barrack-rooms. The men’s kits were laid out. The French Colonel would not believe, when he saw the soldiers’ necessaries, that they would all go into the knapsack, so one was packed to convince him. He expressed himself very much taken with the appearance and turn-out of the men, and well he might be, for without partiality, they are a fine body, and if they only had a good chief (like Colonel Adams of the 49th), they would be one of the best regiments in Her Majesty’s Service.

It looks very warlike, so many engineers of both nations going to the East. General Burgoyne says we are going to send 30,000 troops. I hope we may have a finger in the pie, and that the 41st may have an opportunity of distinguishing themselves. Although the relief regiments are on the eve of sailing from Cork, it is thought there is little or no chance of our going on to the West Indies, but that the corps coming out will be available as reinforcements. As long as France is on our side, they may withdraw four regiments from Malta. To send 30,000 men would require fifty-five regiments of the same strength as those now serving in the Mediterranean.

I have not yet seen the Queen’s Speech, but I hear it mentions an increase to the Army and Navy. If an increase is to take place, the first thing will be to make every regiment 1,000 strong – they are at present 850 – that would only give about 10,000 men. The next thing to be considered would be extra battalions, and they would require more officers. Whatever happens will not do me much good, as those at the head of the lieutenants would be promoted, and they are not for purchase. Handcock has been talking of selling out, but is now wavering; if he does, Richards would get his company.

The Gazette to-day mentions that young Carpenter is appointed lieutenant to the 7th. He now regrets having applied for it, and I hear talks of trying to have it cancelled. It is no promotion for him, as in the 7th he goes to the bottom of twenty-two lieutenants, and if he remained in the 41st, he would probably have been soon a lieutenant, and then he would have had only nine above him for purchase. I hope, if he leaves us, his respected Governor may follow his example; the young one is not a bad fellow, but it is not at all a good thing having a Colonel and his son in the same regiment.

It has been privately intimated to us by the Staff that no regiments go to the West Indies, so we are in great hopes of having a rap at the Russians yet. In a short time our fate must be known.

We had a first-rate party on the 1st inst. at the Maclean’s; it was kept up with great spirit till three in the morning. The young ladies are very pleasant and good-looking, one might do worse than take one for a partner for life. I am afraid the agitation of the Scottish National Association will be overlooked, now that there is likely to be something of greater moment.

The garrison theatricals went off very well; there were some clever actors taking part in them. Last week we had another sham fight. One had to imagine a great deal, as we were not allowed to advance or retire except by the roads, owing to the standing crops, which at this season are well advanced. Swaby is painting me in a shell jacket. Although it is only commenced, they say there is a likeness. The next letter you receive may, perhaps, tell something more definite with regard to our movements. Ask father not to forget the Colts revolver; if we are to be sent to the East, it will be hot and rough work.

The Countess of Errol has gone up to Gallipoli with her husband, who is in the Rifles. Mrs Carpenter, we hear, intends to go with us. I do not think ladies have any business with an army in the field; it is natural that the husbands will not be looking after their proper business.

21st March.

My last would inform you that we are not to proceed to the East as soon as we expected; it is thought we may leave early in April. Lord Raglan will inspect the force here before its departure. All the steamers which brought out the different regiments, have left, so at present there is no means of transport for those here. It is conjectured that the regiments now in Malta will form the 2nd Division, not the 1st, and that the other corps that come out will proceed direct to Turkey, without disembarking here, and that then the steamers will return for us, so that within eight days, after landing the first force, the second will have joined them.

Malta presents a very lively appearance just now, with soldiers in various uniforms of the Army – Guards, Highlanders, Rifles, etc., etc. The General has issued an order that officers are to wear uniform in or near the town, which is a great nuisance, as at every yard you meet soldiers, and the trouble of saluting and being saluted is a horrible bore.

I have met a number of friends, three of whom I had not seen since leaving the Grange School. Anstruther, in the Grenadier Guards, Lock, 50th, and Clayhills, 93rd. I am sorry to say, Tillbrook, 50th, is left behind with the skeleton Depôt; Gandy, 28th, and Mark Sprot, 93rd, are also here, and several others whom I know. Mr Scott Elliott arrived on the 13th by the Valetta, and brought me the revolver; I have not yet been able to give it a good trial. The Dean and Adams pistols appear to be preferred to Colts; nearly all the officers have brought out the former. Mr Elliott dined with me on Friday. I have not had much time to show the party about, as I’ve been for the last week engaged with Minie rifle practice. Twenty-six men per company are to be armed with rifles, and it is thought the whole force will receive them.

Yesterday the 3rd, 41st, and 68th, were brigaded together; it was only a short morning’s work, but still Mr Elliott and party enjoyed the sight. After it was over, I took them round the fortifications, etc., etc. They have, I think, seen all that is worth visiting here and leave to-morrow for Naples; they say ten days is quite enough of this place, and wish to be in Rome during Holy Week.

Nasmyth has returned from his trip up the Nile; he seems to have derived considerable benefit from it, and intends, as the weather gets warmer, to go to Constantinople. His brother was here the other day, but has returned again to the East. He has three years’ leave from India, and is spending it very profitably, receiving £50 a month by corresponding with the Times, and giving them an account of what is going on between Turkey and Russia.

The officers who have come out from England are in rather an uncomfortable state, having only been allowed to bring baggage to the amount of 180 lbs. for a captain, and 90 lbs. for a subaltern, which is certainly precious little, when it includes everything in the way of bedding, portmanteaux, cooking, eating, and washing utensils, etc When we move, I will try and take my gun with me; Nasmyth has kindly offered to take it, but there is no saying yet whether we are to see Constantinople. Our mess is much larger than usual, many officers of the other regiments come to dinner and breakfast, as they have nothing except their rations.

The 33rd and 93rd are under canvas not far from us in the Ravelin. They are to be inspected to-morrow, and the three battalions of Guards (who are in the lazaretto at Fort Manoel) on Thursday, on the Floriana Parade Ground, so they will have a long march round. The 44th, with the two I before mentioned, are the only regiments in tents; the others have all roofs over their heads, and are comfortably put up, considering the accommodation required for the large increase to the garrison.

The hotels and clubs are in great request for dinners. At the latter a table d’hôte has been established, at which sometimes sixty sit down, but I hear complaints about the want of attendance, and that after the dinner is over, some have had little or nothing to eat Everything has risen in price. The poorer classes are complaining much, but some of the tradesmen must be making rapid fortunes; they are working night and day, and yet cannot get through the orders they have received.

The 4th and 77th are hourly expected. The two companies of our Depôt were to leave Dublin on the 11th for Liverpool. We will all be delighted to see them. Pratt and Paterson, late 61st, Lieutenants Wethered and Bertram, and the two junior ensigns, are all that remain. Handcock has gone to England, having sent in his papers. There is a talk of adding another major to each of the regiments composing the expeditionary force, and also another company, making the regiments 1,450.

Since the arrival of the 93rd, I have been out twice riding with Turner. Swaby has finished the likeness he was taking of me; I am not certain that it is very true, but it is good for an amateur, who does not often take up his brush. I will send it home by Mrs Swaby. The Ripon, that brought the Guards and afterwards went on to Alexandria, is expected to-night.

8th April.

My last was on the 21st. There have been considerable changes since then regarding the expeditionary force, and our turn is likely to be near at hand. The Rifles, with General Brown, embarked on board the Golden Fleece on the 30th March; their destination is said to be Gallipoli. Since then the 28th, 44th, 93rd, and part of the 50th have left. The other regiments of the 1st Division are only waiting for the return of the steamers. The Cambria, with detachments of the 50th, 33rd, and 77th from England, has just cast anchor in the Grand Harbour. The Himalaya, with the homeward bound passengers from India, arrived yesterday, she has been detained, and is to be got ready as speedily as possible to take troops; having a very heavy cargo, she will not be in proper order before Tuesday. The Golden Fleece and Emue are expected from the East immediately. Our orders are to be ready to embark at the shortest notice.

We have received our volunteers, with the exception of twenty-six, whom we should get from the 14th on their arrival, but as they have not yet left Ireland, there is little chance of our seeing them. The draft from our Depôt arrived on the 28th. Northey has a month’s leave. Our brigade is composed of the 41st, 47th, and 49th, under Colonel Adams, of the 49th. Every one says it is the finest brigade going up; the reason partly is that we have no recruits, and all our volunteers are trained soldiers.

We have broken up our mess, and the plate, etc., is being packed; my traps are all put up, with the exception of my war-kit. I intend to take a hammock for my bed, as being the most portable; without the blankets it does not weigh 10 lbs. What I propose taking will be over 90 lbs., the regulation allowance, but as a mule’s load is 300 lbs., and one mule is allowed to two subalterns, we reckon carrying about 150 lbs. each. We do not know yet whether we are to provide our own animals or not. Horses and mules have risen much in price; ponies that could have been got here two months ago for £15, are now £25 and £30; a good mule is £30 and £35. Tailors, saddlers, and tinsmiths are in great request for making pack-saddles, valises, camp canteens, portable beds, etc., besides no end of knick-knacks.

I have been trying my pistol. When I received it, the lock was not in good order, so I had it taken to pieces by our armourer, and it now acts perfectly. I much prefer Deans to Colts for close quarters – which, of course, is the only time a pistol should be used – but for correctness of aim at a distance, the latter is better; almost all the officers belonging to the expeditionary force have invested in Deans.

There has lately been a good deal of excitement owing to the arrival of French troops; their steamers all put into Malta to coal, a number of the officers and men are allowed to disembark. It was a lively sight, seeing a British regiment turn out and line the walls, cheering the steamers as they passed in and out of the harbours. The French returned the compliment, but their shout is not like a British cheer. The first detachment that arrived was accompanied by a General, who is to be second in command, and there was a review of the Guards, 33rd, 93rd, and Rifles. The other day another swell passed through, and there was a second turn-out of all the expeditionary force, excepting the 41st, 47th, and 49th. Some of the officers came into our mess-room to have lunch, and were much surprised at our having so many things to carry about with us, and enquired if we were taking them all to Turkey. They were very pleased with the review. Since writing, we have heard that we are to embark on Monday in the Himalaya with the 33rd.

Malta, 8th April.

My dear Sir Hector Greig,

I have long intended to despatch a few lines to you, and I must not delay doing so any longer, for fear of finding myself off for the wars before my intention has been executed. I suppose you have seen by the papers that the gallant 41st is under orders to form part of the expeditionary force for Turkey. Our orders are, to hold ourselves in readiness to embark at the shortest notice, at which we are all delighted and in great spirits. What an agreeable change it has been to us, as we were to have sailed for Jamaica this spring.

For some time back Malta has been much enlivened by the passing to and fro of military (French and English), and Valetta has during the last month been swarming with redcoats. It was an unusual sight to see the British regiments turn out and cheer the French as they came into the harbour for coal. The other day the French General, who is to be second in command, passed through. There was a grand review of nearly all the 1st Division on the Floriana Parade Ground. Such a large body of troops had never before been assembled together in Malta, and most probably such a sight will never be witnessed again. The General and his Staff were much taken by the appearance of the men, the Highlanders they said was a splendid corps. A square was formed by the Grenadier Guards and when the French General with his Staff went into the centre, he remarked that he believed it was the first time the French had ever had the honour of entering a British square.

The French troops from Algeria are a very fine lot. During the last few days, several of our regiment have left this; their destination is said to be Gallipoli. The remainder of the 1st Division only await the return of the steamers. The Himalaya, with the homeward bound passengers from India, has been stopped to take troops, and some other steamers have arrived to-day, and are to be taken up, so we may expect a move soon, and the sooner the better I shall be pleased. Malta is beginning to get too hot. I cannot say that I have enjoyed my residence here much. Old Ireland, bad as it is, is preferable, but we soldiers are never contented.

The last news from Turkey is supposed to be unfavourable, and the troops are to be hurried on as soon as possible, but at present there is no means of transport from here. There is a contradictory report in Malta that the Turks had entrapped the Russians into crossing the Danube, and had then fallen upon and slaughtered a number of them, but there are so many different rumours, it is impossible to know what to believe. I do not think I can give you much Maltese news that would interest you, as there are very few families now in the Island who were here during your residence. Sir Charles Maclean and his daughters are still here. Sir Lucius Curtis intends returning to England this summer; his daughters have not been in Malta this winter. The society has been rather small, and very few nice young ladies; the Maltese associate very little with the English. San Giuseppe, where you lived, must be a comfortable residence, but I do not know Mr Lushington who is now there. Our present General is very pleasant, and exceedingly liked in the garrison. The Governor is a quiet man, and entertains little at this season. In the summer he lives at Verdala Castle; he has done a good deal to improve the Island. My uncle, Colonel George Allan, I expect here on his way to Constantinople about the 13th inst.

The orders have come out, and I see by them that the 41st with the 33rd embark on Monday afternoon in the Himalaya. How fortunate we are getting such a fine large steamer; we shall (at least the men) be very closely packed to stow 1,700 into her. Colonel Adams goes with us. The 47th, 49th, 50th, and 77th, go on board the Indus, Sultan, Apollo, Cambria to-morrow, so the whole of the 1st Division, with the exception of the Guards, will be off by Tuesday. There is no saying what may have happened before this day two months. I hope you may hear that the 41st have distinguished themselves. Our brigade is the 41st, 47th, and 49th, under Colonel Adams of the 49th. Every one here says it is the finest brigade of the lot. We have not a single recruit, our complement being made up by volunteers from the other regiments now in the Malta garrison, who are not going to the East.

All those that are to remain behind are sadly disappointed. I hope the severe winter in England did you no harm; it was a very trying season. It will give me much pleasure to receive a few lines from you at, your leisure. I cannot say what my address may be, but 41st Regiment will always find me, as letters will be forwarded. I must say adieu.

Dardanelles, Thursday, 8 A.M.,

13th April.

I posted a letter on the 9th, the day before we left Malta; it would inform you of our move. Here we are now cutting through the Dardanelles, and expect to reach Gallipoli about noon. We have had a lovely passage – not a wave on the sea, and no sickness on board. This is a capital ship. We weighed anchor at half-past six on Monday evening, and were saluted with no end of cheering from the forts and town. It is now quite a common affair, a regiment leaving for the wars.

The Emue, with the 4th Regiment, left soon after us. Before we were out of sight of Malta, the Himalaya broke down; the packing round the piston required renewing. We were delayed nearly three hours, which gave the Emue a good start. There was a kind of race between the two vessels, as the captain of the Emue, before leaving Malta, had said he was confident he could beat the Himalaya. We passed her yesterday afternoon, and had great fun chaffing her by signal. She is now astern, but pretty close, having come up with us during the night; we went half speed for three hours, because our pilot did not like to enter the Straits during dark. The entrance is strongly guarded by forts, and the current is very rapid, running 3 knots against us. Before leaving, I called on the General to say good-bye; he wished me all success, and said it was a fine opportunity for us young men, and he only wished his health had allowed him to take part.

14th April.

On our arrival at Gallipoli, we were delighted to receive orders from General Brown to proceed to Constantinople, where we have just cast anchor; the appearance of the town is most imposing. We are to occupy the Scutari Barracks, which are on the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus; a thousand Turks are quartered there at present. We are fortunate in being here, for at Gallipoli the regiments are very uncomfortable, encamped on a dreary site. The town there is a poor place, and they have little to eat, and that little very bad. Several of the officers came off to us with haversacks to try and get some additional prog to help their scanty rations. The 4th, 2Sth, 44th, 50th, 93rd, and Rifles remain at Gallipoli for a few days, and then march to a camp, which is being prepared for them 10 miles off, where they are to throw up a line of entrenchments, and there is some talk of their then going on to Adrianople. The other regiments from home are to land here; the French are to encamp outside the city, about 10 miles off. We expect to remain here for a month or more.

I got leave to go on shore at Gallipoli for an hour, and strolled through some of the French camps, and fraternised with their Algerian troops. The town is built of wood; one or two shells would burn it to the ground; the streets are awfully bad. I did not see any of the native women.

We are lucky dogs being ordered up here, but it is very cold and has been snowing all the morning, with a piercing wind; the thermometer is 21° lower than it was at Malta. The last shave is that the S.S. Furious went to Odessa, carrying a flag of truce, and was fired at, and that on her lowering a boat, they fired again at that; so she returned to the fleet, and reported the circumstance to the Admiral, who gave orders for the fleet to weigh anchor the next morning for Odessa, to teach them civility.

We have received intimation that officers are to provide their own baggage animals and carry their own tents, which weigh 50 to 60 lbs. Captains are to take their subalterns’ canteens. We disembark to-morrow, and occupy the barracks at Scutari. I hope to get on shore after dinner. We are the first arrivals here; the 33rd, you know, are with us.

Camp Scutari, 14th May.

We have been here a month, and are no nearer the Russians; we do not know when we are likely to make a move northwards. The on dit is that the Light Division proceeds to Varna this week; it consists of the 7th, 23rd, 33rd 19th, 77th, and 88th, with the Rifle Brigade, under the command of General Brown, who has been replaced at Gallipoli by Sir Richard England. The Rifle Brigade, with the 93rd Highlanders, arrived here last week; they have been working at the lines near Gallipoli, which are expected to be completed by the end of the month. The works extend from the Bay of Enos to the Sea of Marmora; the French also have a large force employed on them. These lines of earth-works are being made in case we or the Turks meet with a reverse, and are obliged to retire. A large number of cannon are to be mounted, so they will be very strong, as the neck of land is narrow. No time has yet been named for any part of the force to go to Therapia to commence the lines to cover Constantinople. They will extend 25 miles, but 13 of that is lake, which will only require to be partially fortified to prevent pontooning.

Lord Raglan or some of his Staff, it is said, sail to-night in the Caradox for Varna; but it is impossible to credit all one hears; for instance, one of the shaves that was currently believed in the city was, that Cronstadt was taken, with the loss of 5000 men and two frigates. The idea of the loss of so many men and only two vessels is ridiculous. One thing I can mention for a fact is, that all the steamers which have brought up troops and stores have orders to remain for some reason or another, and others, now employed in towing the Artillery transports, will arrive in a day or two. About ten large steamers are now lying off Scutari. None of the Cavalry have yet arrived; they and the Artillery will land about 3 miles higher up the Bosphorus, on the Asiatic side. The authorities surely cannot mean that we are all to go from Constantinople into the interior, or why land all on this side and be obliged to re-ship them across to the other, when there are some beautiful barracks near Pera? I think it looks more like a move up to the Black Sea. When on parade on Thursday afternoon, I was delighted at seeing Uncle G and Sylvester L’Amy standing on the square. I have been going about with them a good deal. Last Friday we went and saw the Sultan going to Mosque; he is an insignificant-looking man; he was on horseback, and attended by a number of unmounted officers. The place of worship he attends is close to the palace he is having built near to Torphana. It is not yet completed, though far advanced; the public rooms and the council chamber in it are very fine. The same afternoon we took a caique and rowed to the Sweet Waters of Europe, which is about 4 miles up the Golden Horn. It is a gay sight to see the Turkish ladies turn out in their bright-coloured dresses, and squat down at the edge of the waters. They are all veiled, but some of the veils are very thin, so their features are easily distinguished. The higher classes go about in very peculiar carriages and finely-carved caiques.

Part of the Sultan’s harem was present. Friday is their Sunday; they gather there every week during the summer. On Sundays the Sweet Waters is a great resort for the Greeks. Some of the Turkish women are pretty, but for want of exercise, their complexions are pale and sallow, and they dye their eyebrows and nails.

It will be better in future to send letters direct to Constantinople by Trieste or Marseilles. I have moved out of barracks into a tent in the square, and much prefer being under canvas, as the fleas were dreadful in quarters. It was very wet yesterday, but the rain did not come through my tent. Will you ask father to return my name to Cox for purchase, not that I expect to be a captain immediately. I stand fourth on the list, but there is a talk of an augmentation to each of the regiments out here, of one major, three captains, three lieutenants, and three ensigns, and it is said some of the vacancies will be filled up by officers from half pay, few of whom are likely to remain, so when they sell, the promotion will go by purchase. I may, perhaps, soon find myself a captain, though it is improbable that they will give the four companies to officers at present in the regiment. Our Colonel came from Malta with the 30th Regiment. I am going across to Constantinople to see what uncle intends to be about to-day. Government has provided a steamer which runs every two hours.

Scutari, 25th. May.

Things are now beginning to look a little more like work. The Light Division embark for Varna on the 27th; the Artillery sail to-night. Varna is only sixteen hours by steamer, so before the middle of next week, we expect to be all out of this. A French vessel filled with troops came in this morning; others are shortly expected. Before Monday they say 25,000 allied troops will have disembarked at Varna; a place about 13 miles from the town is talked of as a rendezvous. A magnificent fleet of steamers and transports are at present lying here; it is a grand sight.

The scenery about Stamboul and up the Bosphorus has now become very beautiful; the foliage is fully out, which, contrasted with the wooden houses, gives a fine effect from the water; but the town does not improve on acquaintance. Along the banks of the Bosphorus there is a continued line of habitations; the surrounding country is very barren. I am going up to Therapia to-morrow evening with uncle and S—.

We stop all night, and return by caique in the afternoon down the stream; it is much pleasanter going in a caique than on a steamer, but it is tedious work rowing up, as the current is very strong in the Bosphorus. Uncle George has been exceedingly kind to me, and has given me everything I require for the campaign, including a capital strong baggage horse, which will also do for riding; besides this, he has fitted me out in first-rate style, with a pack-saddle, saddle-bags, etc, complete, which he brought out with him from London. He has also bestowed on me a strong compact stretcher bed. Sylvester presented me with a bridle and riding-saddle, so altogether, my outfit has not cost me much. I am afraid uncle has deprived himself of things that might be useful to him, should he accompany the army, which he purposes doing, if we are likely to have some real work soon.

The Light Division only left to-day for Varna. They went up in gallant style; nine or ten steamers weighed anchor about the same time. They say the 1st Division is to go before us, so probably we shall not leave until next week. I am just as well pleased that we are to be the last, as this place is preferable to Varna and its neighbourhood, and the other troops will not move forward till we are all together. The last accounts from Schumla are, that Omar Pasha says he will resign if he is not assisted, as he will not stand being defeated, which is certain to occur, if the allies do not advance. It is said that the Russians before Silestria lost 8,000 by a sortie from the garrison.

The loss of the Tiger is a great disaster. We hear a parallel case has happened to the Amphion in the Baltic. Last Friday week a sad catastrophe occurred to poor Macnish, of the 93rd. About half-past nine o’clock in the evening there was a deluge of rain. Macnish was returning home to his tent with Clayhills; they had to pass a little drain which runs across the road, and which is nearly dry in fine weather, but this evening it was a torrent. The two joined hands, and attempted to cross the water, but the stream took them both off their legs. Clayhills was taken down about 30 yards, then he managed to catch hold of the bank, and succeeded in extricating himself, but poor Macnish was carried out to sea, his body not being found for several days; probably he was stunned or suffocated by the mud. His sword hilt was much dented when it was discovered; I had been talking to both Macnish and Clayhills that same afternoon at the Sweet Waters.

We went and had a look at the Sultan returning from Mosque on Friday, he has not taken the trouble to cross the water to see the English troops. We had a great turn-out on the Queen’s Birthday, and gave her three hearty cheers. Our Colonel was thrown from his horse, and severely hurt; he is still laid up, and will not be able to accompany us to Varna if we go soon. I am glad to say that Wethered is to be promoted to his company without purchase, but he is going to leave us afterwards, having been offered the paymastership of the 95th; the regiment is in our Division. We expect a run of promotion by the augmentations, but it is not known whether the steps will go by purchase or not. The whole regiment is to leave the barracks, and be put under canvas in a few days. I am going to pack up all my traps and put the pack-saddle on my horse, and see how he goes along with his load. My next letter may be dated within about 30 miles from the Russians.

Camp Scutari,

9th June.

My dear Mother,

I hope you will receive this on the 21st. I cannot allow the mail to go to-morrow without sending you a few lines of good wishes for your birthday! Yesterday I had the pleasure of receiving your letter of the l6th May, along with some other despatches, which, though of rather ancient date, were none the less welcome. It does not do to write to Constantinople via Gibraltar or Malta, as there is no direct communication. Some of the letters were more than a month old.

The Turks are doing wonders; they do not appear to require our assistance. It is reported that the Russians have withdrawn from Silestria, and a rumour is afloat that Sebastopol is the point on which a descent is to be made. Our whole force of Infantry has now arrived. The 42nd disembarked yesterday; the Cavalry and Artillery are joining daily. Four officers of the 4th are here on leave from Gallipoli; they much prefer this quarter. Robertson is among the number, and he says that they want him to settle down at home, but of course he will not retire just now. Poor Gandy of the 28th has broken his leg at the hip joint; he fell from the mast of a vessel, and it is feared he will be a cripple for life. One of the officers of the Artillery had his leg broken by a kick from Brigadier-General Adams’ horse, he is doing well. Captain Wallace was killed at Varna the other day by a fall from his horse.

Five days ago, I accompanied the two travellers to the Princes Islands; it was a pleasant day’s excursion; the scenery is very pretty. There is a talk of moving the camp a few miles up the Bosphorus to the Giant’s Mountain, near Beikos Bay, opposite to Therapia. I forget whether I mentioned having gone up with uncle to Buydkere; it is close to the Black Sea, the view on all sides is beautiful; we took a long walk through the forest of Belgrade.

This morning the regiment received Minie rifles, which, I think, will rather astonish the Russians; the whole force is to be armed with them. The Himalaya has arrived with the 5th Dragoon Guards. Nasmyth has come on here from Naples; he talks of returning to Scotland in a few days, so I will send by him some photographic views of Constantinople and the camps. I frequently see Maitland; he went with us to the Princes Islands; he is a very good sort of fellow. We are anxiously waiting for news from England, our latest papers being the 24th, and we expect the Augmentation Gazette by the next mail. We are to have another 150 men out here. The regiment is to be increased to 1,400 in all, and have an addition of six officers.

16th June.

We are off to Varna to-morrow, per Medway, a first-rate steamer; the passage is about fourteen or sixteen hours. The 1st Division has arrived. There (is no truth about Silestria having either been taken or the siege raised. Things seem to remain much as they were in that neighbourhood. The Light Division are encamped within a few miles of Varna; they were ordered to Silestria and Schumla, but countermanded after proceeding some distance. They say we shall be hard at it the beginning of next month. Our Cavalry and the French contingent are not all up yet.

Uncle George and Sylvester are heartily tired of Constantinople, and went to Broussa, which is a short distance up the Sea of Marmora, last Tuesday; they are to return on Thursday. I think they will soon now proceed to Varna, as the army has left Scutari. One company of the 49th remains behind to take charge of the stores; at first the order was that two companies were to be detailed, and the second named was Richards’ company, to which I have the honour of belonging; he is the junior captain of our regiment. I was in a great state of mind at the idea of being left here, but, happily, it was altered, and I am glad to say we are off for the wars. My address will be 41st Regiment, 2nd Division British Army, Varna.

Nasmyth is on his return home; he took some photographs for me, the one of the camp shows the 41st tents m the centre. The print of Scutari Barracks contains a few tents on the right, overlooking the water, where I was first under canvas; the view from the square is lovely.

Camp Devena Road, 8th July.

Since my last we have had two short marches, only about 8 miles each day, which is not a hard morning’s work; we started at 5 A.M. and had our tents pitched at 8 A.M. The first day was to Caragoul; now we are about 3 miles in advance of the 1st Division, and 4 from Devena, where the Light Division and Cavalry are; we remain here for some days. Nothing is known about our movements, whether we go to Schumla, Silestria, or retrace our steps, and embark for the Crimea. By all accounts, there is hot much for us to do in the Principalities. It is said the Russians have retired on Jassy.

A Council of War was held at Varna two days ago. Omar Pasha and the Admiral were present. I hope Sebastopol is the move; it would be a glorious coup, and do more to finish the war than several battles here. There is a report that the Austrians intend to occupy the Principalities with a large force, which would leave, us free to do something else.

This is a delightful place for an encampment, with a beautiful view of the valley, looking towards Varna Bay and the shipping; over the hill there is an extensive view of the Balkan range; the country is hilly and studded with low brushwood. We have all erected arbours to sit in, which are much cooler than our tents. Uncle G and Sylvester are now under canvas at Varna; they have three Turkish tents, and look very comfortable, but the canvas is not as good as ours. I rode into Varna last Wednesday; they were not then quite ready to start, having only succeeded in picking up one good riding animal for uncle, and Sylvester was busy looking out for another. There are plenty of horses, but they are in poor condition; they hope to get a bullock hackerie to carry their baggage; there is a pretty good road to cither Schumla or Silestria; they will probably go on direct, and not wait for the army. Uncle wishes, if possible, to go home via the Danube and Vienna. Omar Pasha reviewed the 1st and Light Divisions on his return to Schumla.

Yuskakova Camp, Near Devena, 18th July.

I have just written to Wm. Aitchison, in answer to a letter received from him. He wishes to know the most useful traps to bring out here; he had received notice that he would most probably have to leave in August. I have advised him not to volunteer to take anybody’s place, if this state of inactivity is likely to continue. The general opinion here is, that we shall not move a mile nearer the Danube, but that the Crimea or Anapa is the mark; the transports have orders for six weeks’ provisions. Whatever they intend doing this year, the sooner they begin the better, as winter is drawing on apace.

In your letter of the 27th, you ask about the heat. There has been nothing to speak of; this place is a great improvement on Malta, and also on the West Indies, I should fancy; so our regiment has not made a bad hit. This life of inactivity is very weary work. We are still in our old camp, but move a few hundred yards to morrow to be clear of the bushes; it is thought being so near them is unhealthy, and there is a good deal of dysentery among the troops, but not very bad. There has been heavy rain the last few days, with thunder and lightning. Uncle George and Sylvester remained a couple of days here on their way to Schumla. I accompanied them to their first halting-place, Parvada, which is close to the Balkans.

We are all growing moustaches. The Duke of Cambridge asked Lord Raglan if he would grant the permission in orders. He replied, he would not give orders on the subject, but that he would not say anything against it. General Brown will not allow it in his Division. There is a report that the Russians have burned Bucharest, so we shall not winter there this year. The Illustrated News is a great treat out here; I am the only one in the 41st who receives the paper regularly. If the print of Scutari is as like as the one that represented the barrack gate, I think it will be rather difficult for me to point out the window of the room that I lived in; it was on the ground floor, on the left side of the barrack gate, looking up toward the Mosque and village.

This is better encamping ground than Aladeen; there is a beautiful view of the Bay. We have no dust here; it was very bad at the other place, having been first occupied by the Light Division. Yesterday and to-day we had races and sports for the men; there will be horse racing next week. We beat the woods the other day with thirty men; one hare and a few doves was the result of the day’s sport. There are some pigs in the wood, but we didn’t manage to get any.

Yuskakova Camp, 25th July.

To My Uncle.

I have just received your letter by your express Bushibazouk, and was delighted to hear you were put up in such comfortable quarters. The Turks appear to be getting on famously without our assistance. It is just as well that they are not dependent on us, as by all accounts they are not likely to receive any help near the Danube. All the talk is that we embark the first week or so of August for Anapa, and after that is taken, go against the Army in Asia, or perhaps Sebastopol; the Austrians and Turks must look after the Principalities.

At Varna, they are hard at work making fascines and gabions, which looks as if there is something likely to take place soon; they say the fleet will arrive in the Bay on the 28th, and all the transports from the Bosphorus. We are at the same place as when you left us, having only moved 200 yards higher up the hills, to be away from the bushes and the haze that hangs over the camp after sunset. Cholera has been very bad. The last three or four days the camping grounds at Varna and Devena have been changed. The Light Division moved yesterday; they lost seven men the night before, and two prior to that. The French lost sixteen in one day, and several deaths have also occurred in our force at Varna. I believe the 3rd Division were to go to the other side of the lake yesterday.

We received a draft of fifty men this morning; another of one hundred is expected in a few days. I shall then, I fear, be doubled up. I have been fortunate in having had a tent all to myself for so long. Two men of the 95th, who only landed last week, have died; those who have lately arrived from England suffer most. I am thankful to say our camp has been very healthy.

Last week five of our fellows went on leave till the 30th to Schumla and Silestria. I gave Bourne some letters for you; he was to take them to the Consul, if there was no Post Office, as I think perhaps you may have gone to Rustchuk. I was in great hopes that I might have formed one of the party, but the General was scrubby in granting leave to so few. If we are to remain here another fortnight, I may get away in the next batch.

All are heartily sick of this inactivity; it is dreadful being kept so long doing nothing, and having so little to occupy our time; the papers are well scanned, and a great resource. It is difficult to write, when there is so little to mention, and the tents being very hot when the sun shines, so we are driven to the arbours, and there the least puff of wind blows all the papers about, not to say anything of being constantly distracted by the talk and gossip of three or four officers lying on the ground. Some roll themselves up in a quiet corner and try to enjoy a siesta. He is a lucky fellow who can get hold of one of the few stray books, the camp library being very limited.

Yuskakova, 3rd August.

Everything here much the same as when I last wrote. I regret to say some of the Divisions have been suffering dreadfully from cholera; the Light have lost four officers, seventy-five men, and three women; it has also been very bad in Varna, our brigade has only lost one man.

Yesterday we buried poor Maule, who was Adjutant-General of this Division. There is now no doubt but that we are to cross the Black Sea, it is said to Sebastopol.

Sir George Brown was last week close off the stronghold, and we hear a landing-place is decided on, and with comparatively little work, we hope to become masters of their fleet, and perhaps the whole place. It is believed if one crown fort on the north side of the harbour is taken, their fleet can be destroyed.

All the regiments are busy making fascines and gabions. We expect to leave this in a few days, but everything is hearsay.

The last Gazette, I am afraid, has played the mischief with our promotion; we were in great hopes that the step would go in the regiment, but if we are all alive to enter, on another campaign next spring, there will be a mighty change. Weather at present very unsettled; very hot in the mornings, and cold, with heavy dews, in the evening.

Soombay Camp, 18th August.

I suppose you will be expecting to hear from me by this mail to let you know that I am still in the land of the living; as for news, it is scanty, except what is of a sad nature. You will regret deeply to hear of the death of poor Wm. Turner of the 93rd, he died last Saturday morning, and I heard of it in Varna on that day. The funeral took place on Sunday at 6 A.M., I was sorry I was not able to be present. I sent my servant at sunrise to find out the hour, and when he returned it was too late. Colonel Elliott, of the 79th, and he were buried at the same service. The senior Major of the 79th died at Gallipoli on his way to England. We have every reason to be thankful for the good health of our brigade, having had very few cases of cholera or any other sickness. The 93rd have suffered severely, also the Light Division, but I am now happy to say that it is on the decrease. We all think the end of next week will see us out of this horrid country, and I trust that we may never return to it. The preparations for our embarkation are nearly completed, four piers have been constructed on the south side of the Bay, and the large boats for landing are all ready. The Guards, with the 42nd, marched into Varna yesterday, and are to be encamped in a healthy situation for a few days on a hill to the south of the Bay. The remainder of the Highlanders were not able to move for want of transport to carry the sick and the men’s packs; they took two days, marching twelve miles; this will show you what a nice state they are in. The 33rd have 200 men unfit for duty, and the 93rd have 175 sick and convalescent.

There are twenty-nine vessels of war in harbour of different nations. Part of the 4th Division, which is coming, out, have been disembarked at Beikos, a wise move not to bring them up here till they are required. Some of the French Artillery were put on board ship the other day, but cholera broke out, and they were obliged to land them again. The French General, who took the Division up to the Dobrudscha, has committed suicide; he was to have been tried by Court-Martial for losing so many men.

Nearly the whole of Varna was burnt down last week; the fire is still smouldering; a good deal of Government property was lost. There is not a shop left; but you will see the account in the papers. I do not feel up to writing much more, having already written several letters.

Tell Jack to tip me a line when he has nothing better to do, and not to be carried away with the idea of having a red coat on his back; he had better think twice about entering the Army; he can easily find a more comfortable berth, and I should advise him to try and get a more lucrative one. The Army is all very well at home among the lassies, but times change in places like Malta, the West Indies, and an army of no occupation in Turkey. You certainly see something of the world very cheaply, but it has many drawbacks. Honour and glory may be all very fine, but we do not know what that is yet. I hope we may know a little more about it before the middle of next month. To us it seems late to attack Sebastopol, but no one talks of anything else; I rather discredit the taking of Boomarsund before the French troops arrive. It is just as well the editor of the Illustrated London News writes the names underneath his illustrations, as we find it rather difficult to make out the place he has depicted where the troops are in camp; some of the prints are, however, good, and the paper is much sought after.