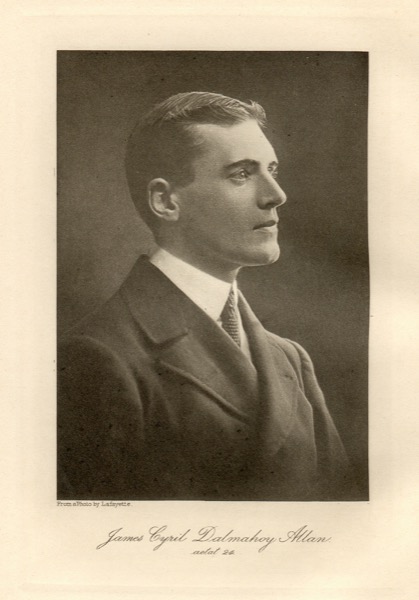

James Cyril Dalmahoy Allan

A Memoir by D.F.

Contents

Foreward

Chapter 1: Edinburgh

Chapter 2: Christmas Island

Chapter 3: China

Chapter 4: France

Chapter 5: The East Again

Hong Kong Recollections: Branksome Towers

An Ordinary Day

Chapter 6: The Last Chapter

Foreward

The name calls up a flood of memories; memories grave and gay, following one another as the waves on the seashore; memories of his attainments, his light-heartedness, of his courage, constancy, and kindness; memories, also, of something less tangible, but as real, of his power to throw a glamour over all he did, and to convert the simplest, most ordinary project into a great adventure.

The news of his death, in Hong-Kong, came with a startling suddenness to his friends, all unaware as they were of the illness which had overtaken him, and the feeling is now widespread amongst them that the spirit of his remarkable personality should not go down to death unrecorded. They, his friends, can never forget him, but they want him to be something more than a legendary figure of happy memory, especially to their children, to whom he was the wonderful Chinese Uncle appearing at long intervals, laden with gifts, and expending himself for their enjoyment. If, thanks to this short memoir, he becomes to these children, even in a measure, the inspiration and delight he was to their parents, this little book will then have served its end.

I am well aware how inadequate I am to perform this task, but the exigencies of work and business debar others more fitted from the undertaking, and it seems better that the attempt be made than that it should be left undone. I would therefore ask his friends to forgive all shortcomings, and to extend to me the clemency which he himself would have shown.

He was many things to many people, even in his name: ‘Cyril’ to his large family connection; but to those whose friendship dated from his student days he was known as ‘Jimmie.’ Each group was quite unfamiliar with the other name, and as a compromise he is referred to as ‘Allan’ in this memoir.

Many of the letters from which this memoir has been taken are those of a very young man. Insufficient in a sense they may be, for he seldom did himself justice, yet to the discerning they reveal the writer and create the atmosphere which makes for reality. An attempt has been made by welding them together to give some sort of full-length portrait of him – no simple matter in the case of a man whose experience of life was broken up into distinct divisions – separate compartments, so to speak – and no one friend travelled with him all the way.

His nature was one of sharp contrasts, and therein lay much of his attraction: the gayest at any revel, yet choosing for himself periods in the wilderness; erratic, yet possessed of dogged, serious perseverance; luxurious to the point of extravagance; but light-hearted in the roughest circumstance; critical but catholic in his sympathies; ambitious, capable, effective, but humble in regard to his own attainments. Many who knew him were unaware of his real worth, his exuberance of spirit and almost baffling levity hiding from them his infinite capacity for taking pains, and his truest aims. It was not his good fortune to make discovery, or to add to the sum total of medical knowledge, but if the art of healing be the physician’s main achievement, then he was a great doctor. Those under whom he worked, the students of his day, and above all, those who looked to him in their need for comfort and advice, held him a man of exceptional ability and power. From innumerable sources have come proofs of what he stood for in the lives of others.

The writing of this memoir has been, in a sense, a voyage of discovery. Even we, who knew him best, scarcely realised what manner of man he was until he left us.

D. F.

Chapter 1

Edinburgh

James Cyril Dalmahoy Allan was born on February 13, 1882, at Ootacamund, India, and was the second of the three sons of Alexander Allan, who owned large tea and coffee estates in the Neilgherry Hills.

Alexander Allan came of the family of Allans of the Glen in Peeblesshire, which now belongs to Lord Glenconner, and his forebears also owned ‘Hillside House,’ which lay in the then open country between Edinburgh and Leith. In the early years of the nineteenth century, his grandfather, inspired with a wish to build something in the new town of Edinburgh which should rival the Charlotte Square of the brothers Adam, demolished the old house, and built Hillside Crescent upon the site. No. 4 eventually passed to Mr. Alexander Allan, and this fine old house remained the family home until 1926.

Mrs. Allan was the daughter of Patrick Dalmahoy, Writer to the Signet, who inherited from his uncle, General Carfrae, the property of Bour-houses in East Lothian. She was one of a large family. Her elder brother, Major-General Dalmahoy, served during the Indian Mutiny, and died only recently, full of years and honour. Mrs. Allan was a woman of rare charm, and was gifted with a beautiful voice. Surely it must have been his mother who passed on to her son his way of winning hearts, for wherever she went she left a trail of happy memories.

After the birth of the youngest child, Mrs. Allan became very ill, and she and her little sons were sent home. She reached England, but died shortly afterwards in London. The three motherless boys went to Hillside Crescent, and were brought up by their aunt, Miss Allan.

In 1892 Allan went to the Edinburgh Academy, leaving it in 1895 to go to Rugby, where he remained until 1900. Shortly before going there he had a severe attack of rheumatic fever which affected his heart for life, and it was owing to the care and kindness of his uncle, Sir Thomas Barlow, that he recovered sufficiently to stand public school life at all. His schoolfellows remember him as a fragile boy, popular with the ‘sixth’ and the older boys of his house (Mr. Donkin’s), but debarred from all games, and they had difficulty in recognising him a few years later – a man well over six feet in height, broad in proportion, and the very embodiment of energy and riotous spirits.

His school life had given evidence of no particular ability, and the state of his heart precluded his entering any of the Services, so what to do with him on leaving Rugby was a considerable problem to his elders. Allan solved it himself by his decision to become a doctor, a decision which, on the face of it, seemed well-nigh fantastic, as the boy had hitherto shown no great aptitude for study or power of concentration, the absence of which two qualities leaves but little chance of success in the arduous profession of medicine. No one guessed that one so gay and irresponsible possessed brilliant ability and the will to plod through the stiffest work. Almost immediately on leaving school, however, he seemed to step into another sphere of health, capacity, and purpose.

He worked hard at Edinburgh University, and there was not a hitch in his career as a student. In spite of work, he had time to spare for much besides, and was a prominent member of both the Royal Medical and Dialectic Societies. He inaugurated midnight fishing parties to Gladhouse, in the Moorfoots, holding a special place in the hearty of ‘Mother’ MacGlashan, the forester’s wife, who mothered generations of happy fishermen in her little cottage by the reservoir. Exhausted friends might sleep along the bank, but Allan could fish all night, ride into town on his bicycle, and be fresh and ready for his classes in the morning.

His coterie included Shepheard-Walwyn, Jack Cox, Stewart Orwin, Reggie Fothergill, Noel Forsyth, George Gibson, Sam Walker, and Chad Woodward, but the leader of every enterprise, the centre of every assemblage, was Allan himself, with his ardent, active spirit, attracting a host of comrades by the spell of his personality, and retaining them by his generous goodwill.

A conscientious but rapid worker himself, he had time to spare in which he could help his slower brethren; more than one friend was guided by him well into the watches of the night through the intricacies of anatomy and kindred subjects. Edinburgh is a good place to be young in, and Allan never missed a ball or entertainment if he could help it, and he had an unusual capacity for doing amazingly long hours of work and play with comparatively little sleep.

In 1905 he passed his final examination, and then went to the Forsyths, at Quinish in Mull, where he spent a long and perfect holiday, fishing and sailing; all was in tune, country, weather, companionship, high spirits. He felt himself ready for anything, even to giving on one occasion an impromptu and vividly imaginative address on the cave of Fingal to a party of tourists who had mistaken him for a guide! This holiday ended, as it were, the first chapter of his life.

His career as a doctor opened happily, as he had the distinction of being appointed House Physician at the Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, assisting Dr. George Gibson, the well-known consultant. His admiration for his chief made the work seem light, an admiration which was reciprocated by the keen appreciation of the older man for his young colleague.

In spite of the fact that the medical profession was now begun in earnest for Allan, it only seemed to stimulate his natural zest and high spirits. Every experience was grist to his imaginative mill. For fires and auctions he had a special penchant. At one auction sale he had a narrow escape. He had ‘popped in,’ as was his wont, to Dowell’s Rooms, when a sale of some importance was in progress. Two dealers and the auctioneer were engaged on a certain picture, and the price was rising steadily, five pounds at a time. Automatically the auctioneer leant towards one dealer and then the other; automatically Allan found himself swaying in unison. Steadily the price rose: ‘Fifty-five on the bid,’ then a swing on to sixty, then to eighty-five – on it must go forever. So when the stoutest dealer shook his head, and the auctioneer suddenly ceased swaying and Allan with him, the shock was so great that he heard himself shout ‘Ninety.’ The auctioneer steadily fixed him with his bright eye, while one of his creatures came pushing towards him with pencil and paper. Not a moment was to be lost. Grasping his hat and stick, he broke through the crowded hall and never stopped running till he reached Hillside Crescent!

His period at the Royal Infirmary passed all too quickly. The Residents at the Infirmary form a ‘Mess,’ and friendships made there are lasting. But never did Mess pull better together or remain so closely knit as the Mess of summer 1906. ‘One figure in this band,’ so writes a member of it, ‘stood out among the others not because of his ability alone, but because of his whole personality. That man was Jimmie Allan. None there were who met him who did not feel drawn to him. As the days of closer companionship followed, that feeling quickened and deepened until eventually he had grappled the whole of his fellow-residents to himself with bonds of affection and esteem, which neither time nor distance, nor even his early death, can ever efface. The chosen leader in light-hearted exploits, he was also the leader in matters of serious import, for deep down in Allan was implanted the call of Medicine, with all that it implies of human understanding and human sympathy for souls and bodies in distress. The call of Medicine was insistent, and that the urgency of the call was borne in upon him in the wards of the R.I.E. is not, I think, to be denied. May succeeding generations of Residents have such another as Allan to inspire them as had we, his fellow-members, in our time and generation.’

Allan aimed at having as varied an experience in his profession as was possible, and when his time in Edinburgh came to an end, was anxious to serve under Mr. Hogarth Pringle, of Glasgow. He had no appointment with, or introduction to, the great surgeon, but simply appeared to see him one day unexpectedly, and in a few minutes the matter was settled. (Allan was always hard to refuse.) He began work at once as House Surgeon in Glasgow Royal Infirmary, finding it very much to his liking, and, what was more to the point, Mr. Pringle also found the arrangement entirely satisfactory. He discovered in Allan a first-class assistant, keen to learn, hard-working, and always giving his best to whatever he took in hand. When at a later date Mr. Pringle learned that he had decided to go to Christmas Island, he tried to dissuade him, confident that he could make his mark in this country.

Dr. Gerard Fitzwilliams was also House Surgeon at Glasgow Royal Infirmary at the same time as Allan, and it was ‘when they faced the rush and turmoil of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary together,’ as Allan afterwards wrote, that they became such firm friends, a friendship which led, some years later, to their partnership in Hong-Kong.

As usual, he spent the holidays in the Highlands, at Longtown, and at Gladhouse. Speyside had perhaps the dearest place in his heart, and often in after years, stifling in his office in Hong-Kong, with typhoon signals up, overpowered with work and worry, his thoughts turned to the beloved Highlands.

Late in 1907 he joined Dr. Noel Forsyth, who had been in practice at Malton in Yorkshire for just over a year. Together they had studied and played, and now together they were to work with equal success. These days, only twenty years ago, of no telephones and no motor cars, when the long rounds over the wold were made in a tremendously high dog-cart, seem almost as remote as the era of sedan chairs! Hard work indeed, but there was no little compensation in the usually peaceful evenings, lying beside a great log fire, sleepy and comfortable, while Allan entertained with his marvellous yarns. Exaggeration, when exaggeration did not matter, was one of his foibles.

His natural clinical sense told at once in the practice, and his genius for making friends helped him here as always. Willingly would his friend have had him remain with him, but to Allan, with his appetite for work, the scope was not big enough for two. Besides this, a wandering spirit had laid its hold on him, the fate of those born in the East, on whom it seems to cast its spell and draw them back again. There was possibly yet another reason – he knew his life was unlikely to be a long one; twenty years seemed the utmost to which he could look forward. Never did this knowledge appear to affect his outlook, but it may have made him wish to drink as fully as he could of the cup of life while yet he had time.

Wiser counsel prescribed more study and research for him, but this again meant dependence upon his father. By chance at this time he had the offer of the post of Medical Officer on Christmas Island, which meant the charge of twelve hundred Chinese coolies and of the small white population in the employment of the Christmas Island Phosphate Company. This offer he accepted, and on June 4, 1908, he sailed for that remote spot, than which it would be difficult to find one more solitary.

Chapter 2

Christmas Island

Christmas Island lies about three hundred miles south of Singapore, and is part of the Straits Settlements. There were times when he felt the isolation keenly, but, as was his way, he made the utmost of it, and found the work more interesting than he had been led to believe by his predecessor. Both in medicine and surgery he found plenty to do. Very few men of his age – he was only twenty-five – would have cared to face such absolute responsibility, and light-hearted as Allan was, he yet took his work with deadly seriousness. Beri-beri, which had been rife, became, largely owing to his care and treatment, practically extinct. This was almost a disappointment, if one may say so, as he particularly wished to study the subject with a view to his M.D. thesis. He read enormously, and achieved the whole of the Waverley Novels, Montaigne’s Essays, Plutarch, Epictetus, everything about Napoleon upon which he could lay hands, much medical reading, histories of India and Burma, and a vast amount of fiction. He also planned and superintended the making of new tennis courts, dispensary, and many other improvements, and joined heartily in all the sports the island provided: cricket, tennis, billiards, swimming, and even ‘soccer’ with the ‘Mandores,’ the Chinese foremen.

His letters will give the best idea of his life upon the island, the first of which was written almost immediately on arrival:

Christmas Island,

July 1908

‘When I last wrote I was just getting into Singapore. I was sorry to leave the Marmora – she was a very steady boat and we had a cheery time on board, and an excellent four at Bridge! It was almost twilight when we dropped anchor, and a steam launch came off from Boustead’s with a very decent chap called Blair on board … I learned from him that I would have to proceed early next morning to Christmas Island on board the Islander, the Company’s boat . . . We dined at “Raffles’ Hotel” and then visited the Malay theatre. Hamlet was being played in Malay! Shades of Forbes-Robertson! He and others who have their own way of portraying Hamlet would have got some new ideas—the Ghost was most realistic, and the band played “Knocked ’em in the Old Kent Road.” . . .

‘I started the next morning. For the first two days it was most pleasant; we crossed the Equator with a fine breeze facing us, steaming under a perfect blue sky and what looked like eternal sunshine, into a sea dotted all over with a myriad of islands, small and very pretty, some quite brick red and bare in the sun, others green and wooded, varied in shape and colour in a wonderful way. At night, hour after hour, the sheet lightning flashed out.

‘On the second day we put in at a small native village in Java – out shot the sampans with their almost naked crews, each with a wide-brimmed hat on. I can see all the colouring now: the green of the palms, the dense tropical vegetation behind, the streak of glaring white sand, the green of the sea merging into deep blue, and the small boats with their crews shining like figures of bronze.

‘They put on board six and a half dozen very wee birdies they call chickens, some ducks, and two miserable sheep – all for the island, being its fresh meat supply. We left them, and after rounding Java Head came misery, and the “not-once-but-again-and-again” wish for death; the boat had no cargo and rolled and pitched to a nicety! No wonder after thirty-two hours of it I was glad when Christmas Island was reached.

‘About Christmas Island I am not going to say much yet; there have been many disappointments as well as pleasant surprises, and now that one is here it is as well to make up one’s mind to accept the former and get full value out of the latter. After all, the will to have a good time, and get the best out of one’s environment wherever one may be, is very much a question of the personal equation. . . .

‘I learn that the Islander does not by any means run once a fortnight; it all depends upon the phosphate. Occasionally on getting here she can’t land and has to go back to Singapore, because there is no harbour here, and only in one spot is there a small bay, but no shelter.’

Christmas Island,

July 20, 1908

‘Last time I promised to let you know something about the island … It is extremely pretty, and were it thirty miles from London, what a rush there would be to see it! The shape is rather like a flattened-out tiger-skin. There is a bay on the north coast, and around it half a dozen European houses. This is called “Flying Fish Cove,” and is the most sheltered spot. . . . There is a garden round my house which I am going to try and make very beautiful, and then a road and a row of coconut palms – all that divide the houses from the sea.

‘Behind the houses the ground rises steeply to about eight hundred feet, the ground being covered with dense tropical vegetation, and at the top of the hill, about a thousand feet up, are the phosphate of lime quarries, of a clean bluish-white stone. Out east from the European part come the office buildings, the mandores’ quarters, the coolie lines, and lastly, about three-quarters of a mile away, the hospital and dispensary. At the top of the hill there are more coolie lines and a small hospital, and at the far side is a fresh-water spring, from which the water is pumped and gravitates down to this side. The rest of the island is jungle, very dense in parts – some of it has not even been explored!

‘I shan’t close this yet, but will stop because the mosquitoes are making merry at my expense – my hands are swollen and one eye closed up; but it soon goes down! We are lucky not to have any malaria-carrying mosquitoes here.

‘I have started to teach myself to swim, a useful art I never managed to acquire, because at home I usually developed palpitations and cramp after about one minute’s effort.

‘It is 6 P.M. now, and as I sit here on the veranda writing, I am looking due west. For about ten minutes there is a glorious sunset, the row of palms shines like bronze, while the background of heaven-touching ocean is brilliant like a blazing ball of fire which quickly dips below the mystic line, and then there follows such a magnificent colour effect in which sky and sea join – purple, orange, and gold. In what seems a moment of time the vision (for so it afterwards feels like) is over, the twilight is as brief, the crickets start to sing, and darkness ends another halcyon day in this island of dreams.’

Here follows his account of a day’s routine:

‘After breakfast, up to the Hill Hospital on pony (two and a half miles), with possibly a game of tennis there, for my new court is now finished, and very excellent it is too! Back to tiffin at 11.30, which consists of chicken or duck (either whole or made into a Chinese “chop”), cheese and fruit, and, as a drink, the most delicious lime-squash made from limes growing behind the house. After tiffin comes the period of rest – I have not yet started a siesta, but read or write or go up to the Magistrate’s to play him at chess. He is one of those who can do the blindfold touch, and is far better than I am, but so far with luck we stand four all. Tea is at 3.30, and is just a biscuit and a cup of China tea. I am growing mustard and cress for this meal!

‘After tea, to Hospital, and do any operations that require to be done, see more coolie outpatients with various injuries received up at the quarry. I have been fairly busy doing small things this last week: several tonsils to remove, one finger and two toes, also varicose veins, and yesterday I did a Syme’s operation. Then follows some cricket or tennis, and another bathe, twenty minutes’ dumb-bells, and so to dinner at 7 o’clock. After dinner we stop at home and read or else visit and perhaps have some music, or go down to the Club and play billiards, poker or bridge – so the time passes, and one is quite ready for bed at 10.30 P.M.

‘Since we came we have had three vessels in, not counting the Islander for cargo, which always livens things up a bit. I have to go on board when she comes into port, and inspect the crew in my “special capacity.” . . .

‘On the 12th [August] I had to let off a gun for “auld lang syne,” so went up to the hill and shot some pigeons; they usually sit on a branch and refuse to move, but on the 12th they rose to the occasion, were flying about everywhere, and I got some sporting shots! On the 14th I started at 6 A.M. and rode out to the farthest point of the island. It is twelve miles long, but as the path zigzags a good deal the ride was a thirty-mile one. One goes through the jungle all the way, so does not get any view at all; the path is awfully rough mostly, and full of roots and crab-holes, but occasionally there is opportunity for a good gallop. On reaching my destination I had, for tiffin, a curry with the Chinese woodcutters, which wasn’t half bad – or else I was very hungry!

‘I have been a little busier lately, and one day had a major operation, which I think is going to turn out all right, but it was done under such awful conditions! The Eurasian dresser absolutely beat the band as regards giving the chloroform! I was surprised on dressing the case to-day to find that it was healing by first intention.

‘Sir John Murray and his daughter arrived by the last boat.’

Christmas Island,

September 21, 1908

‘… Sir John and Miss Murray are off to Batavia to-morrow. I went with him once on one of his several trips round the island on the Islander, and he named one of the points “Allan’s Point,” so there lives for all time one memorial should I die to-morrow!

The voyage round the island was grand! The coast-line is very stern and rugged – high cliffs all round with an occasional lagoon or bay, or beach. Above the cliffs the dense jungle starts immediately, and rises rapidly to eight hundred feet. There are lots of holes and caves all round, and the great waves go rushing in, causing a deep booming sound … In some cases the end of the cave opens by a blow-hole above ground, and then each time the wave rushes in there is a great column of spray thrown twenty feet in the air . . .

Nobody knows who called it Christmas Island, or why. The original name was “Moni,” given to it by a Dutchman, but until about twelve years ago the island lay unclaimed by any nation, and was supposed to be in the Dutch sphere of influence. Eventually Great Britain annexed it, and it is now one of the Straits Settlements . . .

‘As regards more recent news, my garden is fair. The sunflowers and nasturtiums are out now, but the sweet peas are poor. The tomatoes and lettuces are doing well . . .’

Christmas Island,

October 18, 1908

‘This is Sunday. I have just had a letter from an aunt, asking the particular denomination of the Church here. I fear I shall have some trouble in answering the question. There is the Joss House, with its awful grinning gods and its ever present sensation of a “yellow peril” in the background, where doubtless one might pour one’s sins into the sympathetic ear of a Confucius; and then again, there is the Hindoo temple where the Sikhs worship – the low and prolonged trumpeting of their horn is even now calling all true believers to worship, and the Sikhs in their wonderful Sunday turbans and loose shirts are going past the veranda as I write, with their pots of beaten brass – and with them I daresay one might not seek in vain the Comforter. Yet in spite of all this atmosphere of abounding grace, there is none I should care to advance as evidence of godly piety to a Calvinistic aunt . . .

‘To return to terra firma, THEY have arrived!

‘I am sure you are anxious to know who THEY are. I shall enlighten you – THEY are crabs. Each year, for one month, all the thousands of land-crabs visit the seashore for breeding purposes, and it is an extraordinary sight! The males come first, evidently seeking out the way, and later the females follow. Every path is covered by these beasts, with their black shells and red legs and pincers. They come for miles and march steadily on; hundreds perish during the exodus; each time the tram comes down it runs over any number of them; they are so thick they are piled up one on top of another, and on the seashore they are sometimes six deep. I know it sounds like a fairy tale and is hard to believe unless actually seen. I must try and get some photos. At night, if one is awake in bed, one can hear the steady rattle of their armour in the silence all around. They are no respecters of persons, these crabs, but come marching through the house, and cling all over the bath in the morning. They can climb trees and verandas and all sorts of things, and are of all sizes – some quite small and very neat, others are large – all rather repulsive. “Bunda” attacked one, but got his nose caught and set up the most piteous howling! When I caught him he had torn off the claw, but the pincers were still fiercely gripping his olfactory organ. He is daily becoming more lovable and is a splendid house dog, but he is doggy enough to return in triumph with some particularly nauseous treasure . . .’

Christmas Island,

December 27, 1908

‘We have had a perfect scorcher of a Christmas Day! One perspired at every pore, and wished one had twice as many to perspire from – really a parody on a good old-fashioned day. Of course, one did not in the least realise that it was Christmas! . . . Since then, the rain has been extraordinary – simply comes roaring down, and one can’t make one’s voice heard at all. Now it has stopped for a space and I shall go down for a swim, because after the rain the mosquitoes have come out in their thousands . . .

‘What do you think we found in the jungle? A coolie who had been lost for six years! He was fat and well, having lived all the time in a beautiful cave; his bed, upon which he slept much, was of soft feathers, and for food, arrowroot, pigeons, and fish served his needs. He has practically never seen a living soul during all that time, and has forgotten how to speak Chinese—just remembers “yes” and “no.” As to the reason for the exile, he ran away for some trivial offence after having been on the island two months, thinking he would never be forgiven and just die out there. I have him in hospital, but he is really quite fit – quite a weird sort of hermit! He is glad to be back again, and smiles amiably when I percuss his chest.’

Christmas Island,

March 6, 1909

‘To-day is very hot. The others are having their afternoon siesta, a habit I have not yet acquired, and all is very quiet – the air almost tingles with the heat! “Fuzzy” and “Bunda” have sought the shelter of the bathroom, where they lie behind the great earthenware jars which hold the bath-water; even the butterflies have ceased their aerial flirtation and have taken cover behind the papiya blossom; the only sound is the rattle of the phosphate away in the distance as it pours into the overhead bucket; or the thud of a ripe cocoanut falling to the ground.

‘My latest pet is a house lizard that lives under the cruet on the table, and at dinner, if one puts down a crumb, or if a fly drops from the lamp, it darts out like a streak of lightning and captures its food, then retires as precipitately to its shelter in the centre. It comes back every night at dinner-time.

I have had a little more to do lately in the way of active work and acute cases – I wonder if “talking shop” will bore you, but it is all part of “the dreary intercourse of daily life,” as Dr. John Brown says. I had a man with a fractured skull in, upon which I operated and removed the fragments – so far satisfactory; a case of varicose veins upon which I also operated; another badly smashed up hand from a dynamite explosion, and an empyema; also an acute pneumonia, and two bad beri-beris, so that things have been more interesting.

‘At last I have got a two-roomed house, which I have re-roofed and made into a laboratory and museum, and it looks fine with its rows of stains and an incubator going strong in the corner. . . .

‘David, the Magistrate, has been on the warpath; two more robberies to investigate, mutiny among the Sikhs, and a case of attempted poisoning of the whole Malay contingent by means of Jeyes’ fluid in the tea – not a very brilliant conception and quite unworthy of a would-be Madeleine Smith!

‘One night I went round to a Chinese “sing song” amongst the mandores; one played a concertina, another a violin, while the Chinese fiddle and tom-tom were much in evidence. They sang Malay songs with their elusive cadencies, and danced weird dances, and were amusing. I feared to act as a damper on the subsequent gambling, and so left.

‘A sad thing happened to-day. Five coolies were sitting on a ledge of rock fishing, when a wave came up behind them and carried them all in. Two who could swim managed to scramble out, but three have been drowned. I am so sorry; they were such decent fellows. There is a boat out now looking for the bodies. I suppose if the sharks don’t get them it will mean an inquest.’

Christmas Island,

July 6, 1909

‘. . . This very evening I was childishly pleased over a small event. One hundred coolies, whose time is up, are going back to Singapore and China, and the Krani came and told me they wanted to give me a present before they left. I thought it was splendid of them – every one says they are so callous and indifferent, and many of them are not! I absolutely refused to let them do anything of the kind. Good heavens! The poor chaps have hardly got any money at all. But it was the idea of it that meant so much, so we parted with much wagging of pigtails, and a promise to meet in China, and if not there, in the fields of Paradise where there will be ever so much rice to eat, salt fish galore, no work, and lots and lots of red crackers going all day long; and almond-eyed ladies to sit and fan you; plenty of gambling tables at which one only loses when one has a small amount on, and wins when the betting is high. All that seemed to be their idea of a good time! As a matter of fact, they will all be horribly ill on the way to Singapore, and then lose the little money they have got gambling on arrival there – they simply can’t help playing – so having lost their all, they will not get back to China, but will go to a depot and re-sell themselves for a certain period of time, and be sent to Java or Sumatra, poor little yellow men!

‘We are still having wet weather! The meteorological report shows this to be the wettest year in the short history of the island. I do wish it would set fair. So far I have managed to keep down the cases of beri-beri, more through luck than anything else.

‘Post-tiffinic. The cook has secured a crayfish, which “he makee allee one piecee chop-chop.” I wonder if that would convey anything to your excellent Harriet! In any case, the effort was quite “bon” and must be repeated. As I write, a coolie has arrived with a tin of freshwater crabs. They are good eating! He has brought them seven miles from the other side of the island and refuses to take any money. I am overwhelmed with his generosity, and the only way I can repay him is to give him a day off when he next comes and says he is tired; then maybe he’ll go and get some more – happy thought, he shall have a day off once a week!

‘. . . The head Chinaman contractor has arrived this time to pay a three weeks’ visit to the island. He is the absolute limit, and I think the fattest man I have ever seen, in or out of a show. He has the “fat boy of Peckham” beaten both ways from the ace. His short stature accentuates the awful monstrosity of his circumference. He is quite unable to walk more than fifty yards, and has always to sit on two chairs. He seems supremely happy, all unconscious of the fact that one day he will probably burst. I have no idea of the skin’s stretching capacity, but the limit must be reached some time. As a large waist measurement conveys to the celestial mind the idea of enormous brain development (much savvey), he is looked upon with positive awe by the coolies. He really is a clever fellow, and is worth pots of money, with which he is most generous. As a matter of fact, he has offered to increase my salary by five hundred pounds if I stay, but the moth, rust, and mental decay have weighed down the other side of the balance, and I go. Nevertheless I appreciate the offer and the temptation was there.

‘. . . Have done some good operations lately, and the results have come up to my most sanguine hopes, healing occurring by first intention in every case. I have made a few notes on a fever epidemic we have just got through, which I think will have some clinical interest, and shall send them up to the Journal of Tropical Diseases for publication.

‘. . . We have had fine weather now for a week, but the end of the rain was absolutely record-breaking! 15 inches fell for two days in one continuous crash, lash, and splash. . . .’

Christmas Island,

July 31, 1909

‘. . . The other night the diver (a Malay) who was very fond of the bottle, so to speak, went to fish off the end of the pier, and during a gust of wind he fell over, unbeknown to any one, and was drowned. I think he must have fallen flat on his face and had the wind driven out of him, because even when “off the map” he could swim like a fish. His wife sat all day – after the manner of the true Oriental – howling in a tearless fashion, and beating her breast; then she announced she would join him, and midst the loudest shouts, walked into the sea up to the neck, turned, and came out again. Her chief complaint was that he had been fishing a long time and had caught nothing.

‘The next day, with the true versatility and laxity of the Malay woman, she was arranging which of the other Malays would be her husband, and came to the conclusion that her adopted brother, who is my syce, would be the best. There was a fight between him and the boatman! She leaves for Singapore this trip, and then there will be no more Malay women on the island.’

Allan’s friends will recognise the next two letters as specially characteristic of him. Mention has already been made of the contrasts in his nature, but none was more striking than his meticulous care for others and his heedlessness – callousness, one might almost say – where he himself was concerned.

Christmas Island,

August 18, 1909

‘ Here I am, out at Hospital – 3 A.M. to be precise. I am sitting up all night looking after a case of typhoid. Poor chap, I am sorry for him, he is having a rough time! This is the sixteenth day, and I am wildly keen to pull him through, but alas, it is skilled nursing that is required. The reason I am here is simply that I could not trust any one. I gave the Eurasian dresser full directions at 8 P.M., and went home to help the District Officer sort the mails, the Islander having just arrived. I came back at 11 P.M. and found he had fallen asleep and forgotten to do anything. Inwardly I cursed him, but outwardly said that apparently the only way to get satisfaction was to remain and see to it one’s self. He seemed delighted at the idea of an undisturbed night in bed … so here am I, with the patient asleep, writing away at the end of the big ward. At the other end are some coolies asleep on their wooden beds and still harder wooden pillows beneath their necks, and not one of them is snoring! Outside the night is dark and very starry, and as mild as a June day at home.’

Christmas Island,

October 31, 1909

‘. . . The sun is 90° in the shade, and anything you like on the road! A suitable therm-antidote would be more than good, but for the present I have forsworn all tobacco and alcohol, being unable to play tennis or billiards, or to swim. I got a septic wound on the hand and it was apparently healed, when the glands in the armpit became like the proverbial pigeon’s egg, and the temperature rose by leaps and bounds to 104°, while amongst the grey matter inside one’s head castanets kept time to the devil’s clog-dance. I thought of you and put on anti-phlogostine! During the night grinning gods and disease in monstrous forms visited me in the snatches of sleep, the last one of whom turned out to be the hairy head of a Sikh, who salaamed and seemed much excited. When at last I realised he was in corpore, and I was on terra firma, I mildly suggested he might choke himself as my temperature was still 103°, and then I grasped that a coolie had died with dramatic suddenness during the night, and that I had somehow to struggle on to a pony and go out and do a post-mortem!

‘When I got back I went to bed and awoke better, but almost sure that the case was one of fulminating cholera. I could recollect little about the post-mortem, but I knew I had made some slides (cholera, by the way, was raging at Batavia and the Islander had touched there, at Anjer, and was not put into quarantine, so I have had cholera on the brain). However, the slides had been removed and cleaned by a coolie full of excessive zeal – the man I told you about, who was in the jungle so long – and so I was at a loss and started to disinfect everything, and take weird precautions. Nothing more has happened, so it must have been unnecessary – nevertheless, it was good practice!

‘I am quite fit again, but I can’t do anything with the arm yet.’

Towards the end of 1909 he began to feel that it was time he made a move; that one and a half years on a small island was long enough for his soul’s good. He wrote on November 25:

Christmas Island,

November 25, 1909

‘With luck you should get one more letter from the island of dreams. As I look back, I rather shudder to think of the time I have wasted; my thesis is as airy and unformed as the mystic rat floating in the air. However, I was pleased to see in the last number of the Journal of Tropical Medicine an article I wrote on “Dengue” or three-day fever. . . .

‘On Saturday night, the poker game was disturbed by the arrival of a Malay with a mighty cut on his head, and I had to take him out to Hospital. He had been set upon by a gang of Chinamen, while fishing. Alas, the man that dealt the blow was my own coolie, and I had to go up and give evidence before the District Officer. The prisoner and three compatriots each got three months’ hard labour, so now my coolie passes my house on his way to work, clad in prison weeds, and when I meet him he hides his face in his hands. I did not think there was so much shame in him!

‘The present Corporal of the Sikhs leaves by this boat, and as I have entertained him once or twice, he is coming to say “good-bye” with full honours. I am apprehensive . . . three is the hour of the ordeal. Dressed in all his “glad rags,” with his fellows, he will present me with a bouquet and then offer me a bottle of gin and of whisky. I shall accept the flowers, stand them all drinks, and then they will proceed to fall on me with sprays of the cheapest of cheap scent, and spray me, head, feet, and body. I have been through it before – do you wonder I flinch?

His last letter of the period is dated December 13, 1909, just before his departure from the island. His own words convey a faint idea of the affection with which he was regarded by the coolies, to whom Fate had sent him to minister.

‘I must tell you about yesterday, in spite of appearing egotistical. I wouldn’t if I didn’t know that you will like to hear about it.

‘At 4 P.M. a great mass of coolies and mandores arrived, the head “Towkie” as interpreter. Their approach was heralded by a continuous roar of Chinese crackers and beating of drums. They all gathered round the house, swarmed over the veranda, and a perfect fusillade of crackers followed. When silence reigned again, the head man read an address, and then presented me with a gold medal from the Chinese of the island, along with the most gorgeous banner imaginable; bottles of whisky and beer, etc. Then they all shouted and roared, and when the hubbub was over, I made a speech through the interpreter . . .

‘No one need speak of Chinese ingratitude to me ever again. I think they are splendid little men, and I do wish I could do something in return. It was all so absolutely spontaneous on their part!’

On January 17, 1910, he sailed from Christmas Island, and so ended his first term in that distant part.

Chapter 3

China

On leaving the island, Allan went first to Singapore, where he was entertained by friends new and old, and thence to Malacca as the guest of Alfred Burn Murdoch, Conservator of Forests, who tried hard to persuade him to settle either at Kuala Lumpur or Malacca. Both these places, through a rise in rubber, were awakening from the age-long sleep into which they had fallen since the picturesque days of the Portuguese domination. Wherever he went and whatever he did, his friends tried to detain him, which was his best excuse for being rather a poor timekeeper.

From Kuala Lumpur he went on to Penang, Rangoon, up the river to Mandalay, and on to Shan Hills, a remote and lovely little spot, including in its attractions the necessity for fires, the possibility of a cold bath, and the sight of roses growing. It takes a spell in the tropics to make one appreciate what these things mean.

His letters show the quick eye for the unusual, the observant delight in the beautiful, and above all, the merry heart of a youth who has escaped from exile. But space does not allow of their inclusion in this short memoir.

He found it hard to leave Burma, and envied a family of grey long-tailed monkeys which came crashing through the branches in this ‘Paradise of nuts and fruit and beauty away from the worries of life,’ and he wondered ‘if man having discarded his tail has scored so much after all.’ Allan might have dallied even longer, but fortunately there was much to entice him on.

In April 1910 he arrived at Coonoor to stay with his father. Britain pays a heavy price for Empire in the separations between parents and children which her distant dominions demand. Authority and dependence, two binding links in home life, become unsoldered by long absence, and re-unions are seldom painless pleasures. Many years had passed since Allan and his father had met, and the son was now a man and not a boy, but dissimilar as they were in almost every respect, they were at once on easy terms, each being well endowed with tolerance. To the end of his very long life, Mr. Allan had a strong hold on the affection of his three sons, and they had a deep respect for his simple goodness.

Three months slipped away as a day at Coonoor, but during all this season the future was troubling him somewhat. Shortly after joining his father he had broken to him that he did not intend to return to this country. His father suggested that he should seek advice from wise counsel in London, but this was the last thing that Allan wished to do. Counsel would say ‘Go home,’ without weighing up ‘the joy and fascination of the East, and how it gets hold and grips one’s heart.’ Two months later he had come to no decision, and on June 26, 1910, he writes:

‘Still here, a vacuous idler, picnicking and dancing without a single serious thought, yet knowing, with all the fatalistic superstition of a Buddhist at his wheel, that the pendulum of compensation must swing remorselessly the other way. Still, I hesitate to give it the necessary flick, which an inherent spasm warns me I shall undoubtedly do, the day I leave here.’

The ‘necessary flick’ came a few days later from his friend of Glasgow days, Dr. Gerard Fitzwilliams, who was already in practice in Hong-Kong, and who now wrote offering him a partnership. The offer was accepted, and Allan left Coonoor early in July.

But his holiday was not yet ended! He first visited Ceylon, combining two pleasures: a meeting with his old friend Dr. Cox, and some trout fishing in a river which reminded him of Perthshire. From Colombo he sailed to Singapore, just touching there before going on to Dr. Weber, the Medical Officer to the Sultan of Johore, and from there he went to Java. Finally he paid a brief visit to Christmas Island, returning to Singapore, where he embarked for Hong-Kong. On the voyage thither he writes:

‘It will be good to get to Hong-Kong – it is such ages since I heard from any one! I expect to have a thin time at first, but hope eventually that things will pan out all right. I am looking forward to this new move with a certain amount of apprehension, but it will be good to get back to work once more – I only hope there will be lots of it. I’ve been just horribly slack lately, but it has been a glorious holiday, and something infinitely good to look back upon.

‘I crossed from Singapore by Dutch Mail to Batavia, and so up to Buitenzorg, where there is the most beautiful botanical garden in the world, just a wealth of tropical flowers and foliage. Java, I imagine, is as near to the Garden of Eden as any place I’ve yet struck. I eventually went to Anjer, and caught the dear old Islander. Thirty hours later I was back again on Christmas Island. Of course I visited all the old haunts. My dear old friends, the coolies, came down the last night and gave me a tremendous send-off with fireworks and crackers, quite of their own accord, and I had to shake hands with all of them. They are just dear little men, and I never want to have nicer people to deal with. I got my books and instruments together, and left for Singapore with, I confess, the devil of a lump in my throat.

‘This is an old boat, chiefly cargo, but a good seaworthy one. She is full of dynamite from stem to stern, so we don’t sneeze!’

Dr. Fitzwilliams, when Allan joined him, was living in a flat on the Peak, and this they shared for some months. Allan was now to experience for the first time how competitive life is, and, like most young doctors starting in new surroundings, he was concerned with the want of work, or rather of remunerative work, for he found plenty to do at the Chinese Hospital, where he was always welcomed by the Staff. Very soon, however, he began to make headway with the practice.

Possibly the key to his power to interest and arrest people was his own unflagging interest in everything, including himself. It was alien to him to be negative or indifferent or apart from his surroundings. No sooner did he find himself in new circumstances than he began to put out feelers, light tentacles, which in time became grappling-irons, and within a week or two of his arrival at Hong-Kong he was immersed in his new life.

Pleasure in possessions and the joy of collecting awoke in him at this period, and he commenced to accumulate Korean brasses and ivories, and very soon his flat was filled with china, books, and pictures, to say nothing of his ‘menagerie.’ Children were a speciality of his. He seemed almost to cast a spell over them. If he sat down in a room where they were, in three minutes they were all on top of him. To them he was the magic man who could turn out a tale whenever one was wanted, and who allowed them to do things tabooed by other elders.

‘He is the most sensible grown-up I’ve ever known,’ a little cousin said of him! When he had time for nothing else he managed to write long letters to small adorers in almost every part of the globe. It is pleasant to remember that he had the same attraction for Chinese children, and in the houses of his Oriental patients there were many who called him ‘Ah Shunk’ (Uncle). Next to children, animals were his best playmates; first and foremost, his dogs, but grateful patients, knowing his tastes, used to bring him every kind of pet, till the flat overflowed and he had to pass them on. At his house a visitor never knew what strange creature might appear; a large white rabbit would pop out from under the sofa, or his favourite monkey that lived on the veranda. He possessed a famous Siamese cat, besides birds and dogs galore, all of which were carefully looked after and apparently harmonised.

But while to the casual acquaintance he might seem the light-hearted care-free trifler, the other Allan, the serious, plodding, ambitious man, was working hard and studying. Within a day or two of his arrival he began to learn Chinese, and was to become one of the few foreigners who could make an excellent after-dinner speech in that language. Then when he first arrived at Hong-Kong he was deep in his M.D. thesis, and was very soon appointed Lecturer in Practical Pathology in the School of Medicine.

The following excerpts from his letters give some idea of the various claims upon his time and energy:

31 Queen’s Road Central, Hong-Kong,

September 11, 1910

‘Things here are much as usual, and we are still having plenty of mist. Fitz’s office is down in Hong-Kong, but we live fifteen hundred feet up on the Peak, and to get here we come up in a weird tramway, pulled by a cable up a gradient like the side of a house. The house is a very little one, and from the veranda one looks down hundreds of feet on to Hong-Kong lying below. The view is really lovely, and the bay perfectly beautiful. At night when all the lamps are lighted, it looks like fairyland. We have been quite busy altering the arrangements of the drawing-room, to meet the eye of both of us, and I think the result is a success.

‘I haven’t summed up the pros and cons of the place yet, but as far as Hong-Kong itself is concerned, I like it, and have met some very jolly people. There won’t be much work for me at first, but time will not hang, because they are short-handed at the Government Civil Hospital, and I spend all my mornings there, seeing tropical diseases, doing X-ray work, and giving chloroform. Last week I did a couple of decent operations, all of which helps to keep one au fait. Then I must settle down to a thesis of sorts, and am going to learn Chinese.’

September 24, 1910

‘Three elements are struggling to disturb the even flow of this epistolary effort: first, the wind is sweeping from the north and rattling the windows in their sockets; second, the dearest of chow puppies is dragging at my lace; third, I made this morning an abortive effort to commence my thesis, and the effort has caused profound depression.

‘After this preliminary outburst, I was called away, and now return to the attack. The wind has increased in violence and typhoon signals are up to say that one is within three hundred miles, and so the house is all barricaded up, with bars across the windows, and padding against the glass.

… I wonder if I have anything to tell you. The American China Fleet is in the bay, and I dined on board their flagship New York last night. I had met most of her officers at Singapore, and so had quite a good time, and four of them are dining with me to-night. Amongst other things, they keep a cinematograph on board, and rolls and rolls of films, and they work it on deck, and all the bluejackets sit down and look on. It was working last night, and behind me I heard an ominous groan. I looked round, to see the shade of Nelson in torment. I murmured, “Rest, perturbed spirit, this is not Britannia’s Navy.”’

October 12, 1910

‘To-day is memorable! I had my first lesson in Chinese. It is an appalling language, and makes me feel violently ill. I am sure I cannot master it, but I do want to do so, ever so much, and see vast ages stretching before me trying the tones as they fall from the lips of the “Wisest Man on Earth” as I have nicknamed my teacher, and he certainly looks it.’

October 16, 1910

‘. . . The awful language, of Chinese, it is appalling, and at present one’s head swims with sheer inability to make five tones out of “ng,” all different. My teacher speaks no English, but beams at me over his glasses in a most celestial manner and grunts with approbation.’

October 31, 1910

‘Fitz is reading Vittoria, and all is quiet. I have fifty Chinese characters to learn for to-morrow, so this must be limited. Boonda, my chow, is replete, and a fine breeze blows from the nor’-east. The weather just now is too glorious for words, I have never felt anything like it, and the colouring all round is a thing to dream about. So far, I would not change Hong-Kong in winter for any other place I’ve ever struck – even dear “Auld Reekie”!’

Considering all he was attempting, it is not surprising that his heart began to bother him during the winter (1911-1912), but he managed to get away on a shooting trip up the West River, in January, which soon put him right. As was his way, every moment of his day was filled, and in March he wrote:

‘I make no excuse as to the poverty-stricken state of my letters, but every moment I have is taken up with my thesis, as it is going to be the devil of a job to get it finished and bound and sent home by April 30. … Things here are much as usual. I have added to the burden of life by being appointed Lecturer in Practical Pathology to the College of Medicine here. It is just about as much as I can manage, for I have to go to the different mortuaries and get specimens and mount them myself, which entails endless time.’

And again, a little later:

‘I sent my thesis off last Tuesday, and was glad to see the last of it’ [this thesis, by the way, gained some distinction] and now I must weigh in with my Chinese, also the preparation for my Pathology takes up a good deal of time. This has been a strenuous week. I go down by the 8.30 tram in the morning, and have not caught anything earlier than the 7.50 P.M. up again. The German influence here and in Canton and all up the coast grows stronger every year. The place is riddled with her spies, and all the premier firms are joined in one vast co-operation to push German trade and oust Britain. The more one talks to Germans, the more certain one becomes that the rupture is absolutely inevitable – they all look upon it as a foregone conclusion and live and pray for it.’

In his letters he frequently refers to the German menace, which presumably was more evident in the East than at home.

Much to his pleasure, Allan was appointed Medical Officer to the New Territories (outlying districts), for his duties took him away from the worries of general practice to beautiful and unfrequented places, affording unusual incidents and experiences which were as nectar to his adventurous spirit. He wrote:

‘I left Hong-Kong so precipitately as to suggest that the arm of the law was out after my blood, but I am really quite innocent in the meantime of any direct contravention.

‘So here I am, struggling to write to you, with a very vile pen, on the very trampiest of tramps, and in the distance are the hilltops of the island of Hainan, to the capital of which, Hoi-How, we are bound as fast as the rattling old engines of this craft can hurry.

‘The ship was built at Sunderland, is owned by a Norwegian, and chartered by Chinese. As a result of this hybridity, the crew are Chinese and the captain and officers Norwegian, and their means of conversation with the crew, English. The captain is a very decent soul. I always have liked the Norwegians, and he adds to my esteem of them. He has been married six years, and writes a letter every day to his wife – 365 a year – and she does the same. The great difficulty is to try to get the boat down without cholera or smallpox breaking out on board. All the last few coolie ships have been held up in quarantine, so I am going to be very wide-awake at Hoi-How.

‘Later. After arrival at Hoi-How, we remained at anchor in the bay all one blistering day; the sea was dead calm and there was little noise, save the occasional Tattle of a hawser or the creaking of a sampan coming alongside; there was nothing to be seen – one hadn’t time to go into the interior, which is inhabited by wild, semi-cannibal tribes. On board, I sat and read, while the sun beat down on the awnings and the flies buzzed incessantly. Later, the coolies came on board with a rush, and then the world awoke and pandemonium reigned. Every nook and corner is occupied by prostrate coolies of all ages, from wee children to old men. I examined each one and refused five. Smallpox, cholera, and plague were all bad in Hainan.

‘At last we set sail. The first day out was rough, and it was one of the least pleasant of one’s experiences to go round the holds, which were stuffy and smelly, and crammed with coolies in various stages of mal de mer, while all the time one had the strongest desire oneself – I leave the rest to your imagination! Amongst smaller inconveniences are the cockroaches, which are in their hundreds. I killed forty in my room last night – many as long as three inches. They fly about one’s cabin and crawl about one’s face and body in a most affectionate way, and I loathe them all the time. Then the bed is like a solid board, but the food is quite good, the crew very cheery, and I am feeling heaps fitter for the sea voyage, and sleeping like a top.

‘Now this is the last night and to-morrow we are into Singapore again. … I have examined each coolie every day and isolated a few, but am glad to say we have got through without any cholera or smallpox so far. There have been a lot of wounds to dress, and teeth to extract; we have had malaria, measles, and chicken-pox of all things, as well, so we have really been quite busy. I have arranged the ship’s drug-store, and drawn up a list of drugs and their doses and uses, and read two medical books that I have long wanted to get through, and so have not done so badly!’

By May he was back again at Hong-Kong, ‘fairly settled down again after my trip south, and my Pathology class takes up a great deal of time – were I busier in practice, I could not do it. Next year it will come into the hands of the Professor of the new University, a man who will come out from home, and I shall be glad to hand it over, although I am afraid it means that, at least in the meantime, I lose any chance of getting on the teaching staff. However, I am thinking of starting as a freelance, to lecture on Applied Physiology and Simple Medicine, so that perhaps some day I may get a billet.’

This hope was realised, for, when Hong-Kong University, the great project of Sir Frederick Lugard, was opened in 1912, Allan was appointed acting Lecturer in Medicine. He had a real gift for imparting knowledge, but until now he had only practised it on friends in the throes of examinations. The two following letters show that his Chinese efforts had not been fruitless, or he could not have enjoyed the entertainments he describes:

June 10, 1911

‘On Tuesday I went to a Chinese dinner. This time it was a private one, and the food was beautifully cooked. The women of the house, in their native costumes, were at one end of the table, and the men at the other, and we were not supposed to talk to them! The dishes were most expensive ones: bird’s-nest soup, shark’s fins, walnuts buried in pounded duck, peaches, nectarines, etc. We began at 7.30 P.M. and rose at 10.45, up to the eyes in food, and I confess I was feeling distinctly unwell next day. Towards the end of the feast they bring round a glass of native wine – “Sam-Soo” – and also a bowl of plain rice. The proper thing to do is to let the rice go past and drink the “Sam-Soo.” If one helps oneself to the rice there is consternation in the heart of the host, for it means one has not had enough to eat. As a matter of fact, I could not have eaten a single grain of it if I had been paid for it … Well, I must dispatch this, as my Chinese teacher has arrived. I have started struggling again with the language, and am full of resolve to get the better of it.’

And in September:

‘Last Monday I went to a very fine Chinese dinner, given to Fitz and me by a grateful patient, who gathered all his nearest and dearest around him to fete us. It was unique. I spoke Chinese to the best of my poor ability and had a thoroughly hearty time. He was a dear old Chinaman, and the whole thing was a huge success!’

The Nationalist Movement in China was in its early stages in 1911, and Canton its headquarters. As will be seen in the letters which follow, his sympathies were entirely with Young China in its effort to throw off the Manchu domination. In May he says:

‘The Canton Rebellion is quieter than when I last wrote. A large number of Chinese have been killed on both sides, but the movement is not anti-foreign, and no European has been injured. The ruling Manchus managed to terrorize the rebels; one method was to execute them in boiling oil – it starts cold, and gradually gets hotter and hotter, taking two hours or more to kill. It doesn’t sound a jolly death, but they tell me that some men never cry out once!

And in October:

‘The Revolution is spreading all over China, and will probably soon be more extensive than the famous Taiping one that Gordon squashed. It is, more or less, a unanimous move on the part of the real Chinese to throw off the bond of the Manchus. These latter have kept China back in the dark ages, and resolutely stamped upon any attempt at reform, and the time must come, sooner or later, for a change if China is to keep her place among the nations of the world, who are only too ready to step in and partition the whole place up. At present the rebels are winning all along the line, and will soon be advancing on Pekin itself. I think it is generally recognised that the whole business is a most excellent one for China, and will lead to reform, whatever happens. The corruption among high officials is too ghastly to contemplate; an instance is shown at the battle of Hankow the other day, when it was found that the Imperialist troops were firing wooden shells. The excitement amongst the Chinese in Hong-Kong is intense. The insurrection broke out in Foochow last night, and at any moment Canton will be up in arms.

‘I was having supper with some Chinese in one of the big Chinese restaurants the other night, when suddenly a telegram arrived from Canton. Every one rushed out into the street, and the place was thronged with a surging mass of men. It was quite an effective sight as I leant over the balcony of the restaurant, looking down on the eager crowd below, under the light of the swinging Chinese lanterns. Then as the news spread around, cheers went up on all sides. Eventually I learned what had happened. The new Tartar General, who had passed through here the day before, on his way to take command of the troops, had been most effectually killed by an enormous bomb dropped on him from a roof-top. Thus China reforms; whereas five years ago they hardly knew what a bomb was, they now make them big enough to blow up two hundred people, and set a street on fire.’

Stoical as he was in adversity, Allan had an acute appreciation of the value of comfort – indeed, of something very like luxury. He possessed what a poet has termed a ‘Babylonish heart,’ and the following letter shows how much his surroundings affected him:

‘My room is now assuming extreme comfort. There is nothing wildly original about it; the walls are pale blue, and the big soft Chesterfield sofa and the arm-chairs are covered with Japanese crepe of the same shade, with dark blue cushions. The floor is teak, and is at last properly polished. In the process of getting it done I have, however, lost a good coolie. He struck at the polishing and got lazy, then openly disobedient, and then just exactly two minutes later he was out in the street. It rivalled the transit of Venus in its rapidity, and I felt a glow of virtuous wrath after it was all over. It really is quite a pleasant sensation to seize a large-sized coolie by the back of his neck and run him out of the house. A successor turned up next day.

‘Well, to bore you further with the room, the floor is polished teak, and I have a small Tientsin carpet, rather nice, deep red with a border of dark and pale blue. The rest of the furniture is polished teak, the only exception being a fine Chinese screen, black lacquer with veins of fire running through it. It is really comfortable, plenty of room about it, and makes me realise more than ever the comforts of bachelordom. It is a selfish existence! I prowl round the room every morning in a large bath-towel, on my way to my bath, and am much worried if everything is not exactly in its place. The veranda runs right round, and is fine and broad, and I have a gardener who comes in daily and keeps a large selection of palms and flowering plants going.’

From this description he turns to the troublous times he was living in:

‘The Rebellion is spreading like wildfire. Last night the streets were pandemonium, because news had arrived by Chinese sources that Pekin had fallen. I don’t think it is yet confirmed, but they are wonderful people for getting accurate news. Canton won’t be long now, and I think the Manchus will make a stern fight for it. They have threatened to burn the whole of that huge rabbit-warren of a city to the ground, and they can do it. I hope to go up there next week, as I believe, with the present exit going on, silks, etc., ought to be going cheap. If you don’t hear from me next week, you will know that I have got held up there. I think it would be splendid if the Revolution started while I was there!’

This finishing sentence shows how really youthful the subject of this memoir still was – temperamental too, for in a letter written at the very end of 1911 he says:

‘My Chinese lilies are out in time for Christmas, weeks ahead of any one else’s, potfuls of them, growing in pebbles. Then, yesterday, a consignment of old Korean brass arrived. I have had a man up in Korea collecting it for me and others, and some of it is really splendid: old temple candlesticks, three feet high with butterfly windscreens; old habaschis and bowls. The coolies will be kept hard at it polishing.

‘It is strange how quickly one’s existence is forgotten by people at home. I don’t think I have been very slack about writing, but I have had few Christmas letters, and one realises that the longer one stays out, the fewer ties there are to take one back, until they cease to exist altogether, and then it is only the love of one’s native land, the smell of the heather on a hot day, or the splash of a trout on a summer’s evening, that drags one home in the end. This is morbid, and I must switch off.’

The opening of the University was an important day in the history of Hong-Kong, and Allan duly appreciated its significance. ‘It was a big show,’ he says, ‘and Fitz and I made ourselves horribly conspicuous, as we were the only people who wore robes. We got them out specially and were jolly well determined to wear them. The M.D. robes of Edinburgh are the most startling scarlet, and I can tell you there was an absolute hush throughout the building as we strolled up just before the Government party. It took a lot of courage to do it.’ Later he writes : ‘I rushed up to Canton yesterday, and had a busy day seeing Chinese doctors and dispensaries. When quite tired I went back to the Shameen and dined and slept on board H.M.S. Clio, where Orwin is Surgeon. Had a cheery evening and caught the early boat back this morning.’

In August 1912 he writes: ‘I hear the snipe are in, and I am going to have a day at them one day next week. It will be top-hole to get out of this place if it is only for a day; as Government Medical to the New Territories my duties take me out occasionally to the out-stations, and I shall see that they take me out to a place where there are snipe, and that right soon. I go out and stop with the Police Sergeant, and will be able to rise at the very crack of dawn and get down to it.’ In November he writes: ‘Now the birds have all flighted south, and there will be no more shooting until the winter snipe come in. That is the time I enjoy, going away up the West River for two or three days in a house-boat, shooting all day, blue sky above and a cold nip in the air, and a dog-tired feeling at night, lying on deck smoking a contemplative pipe before turning in and watching the moon come up behind the paddy fields, knowing that there is going to be an early start at 4.30 A.M., in the dark, to try and get at the flighting duck. Then, indeed, for a season, one lives.’

During 1913 the pressure of work increased. Allan had several private anxieties of his own; he was not well, and suffered both from insomnia and from his heart. He often longed to get away from Hong-Kong altogether, but it was naturally more and more difficult to take a holiday. However, in January 1914 he managed to get away for a short time on a contract job, in charge of a ship full of coolies, and went north to Swatow, where he had time for a week’s shooting trip up the river in a house-boat. The insomnia disappeared, and he returned to work keen and refreshed.

The letters which have been quoted tell us something of his life, but only a limited part of it. From them it would not be gathered that he had in three years developed into a personality, almost an institution, in Hong-Kong. But such was the case. He had made his mark as a surgeon, and patients of every class, one might almost say of every colour, had come to depend on him. ‘No white doctor has ever had such a following as he had, and probably never will again’ (I quote the opinion of another well-known doctor in Hong-Kong). He inspired patients not only with confidence in him, but, what is rarer, with confidence in themselves, helping them morally and physically to face facts courageously, for it is a merciful fact that vitality, like depression, is infectious. Like every good doctor, no case was too small for him, no patient too poor, and he would take as much trouble over an unfortunate coolie as over any one else.

There are 365 days in the year, and it is impossible to do kind deeds every day of the 365 without its having effect. In his three years at Hong-Kong, Chinese and Europeans alike had come to look upon him as the unfailing friend who might be counted on whenever difficulty arose. There is a Persian proverb, ‘A friend is one who knows all about you, and is still your friend.’ Allan was a true friend, for all he knew never affected his friendship. He refused to judge man or woman, and again and again the sick and penniless were taken to his flat, nursed well again, and sent on their way with money in their pockets with which to make a fresh start. He was a ‘saint without a conscience’; his goodness was unpremeditated and had no ‘ought’ about it; it seemed as natural for him to help a ‘dead-beat’ of another class as to arrange a trip with one or two friends on Sundays, going in rickshaws with the dogs up into the hills behind Kowloon city, away from everything and everybody.

Towards the end of 1913 he wrote:

‘The B.I. Line, who have at last got a hold in the China coast, are pushing the Japs out of it somewhat, but everywhere the ubiquitous German is working ahead, forging on to being the dominating military, naval, and commercial power of the world; that WAR is bound to come; to what good, if any, remains to be seen.’ He had little idea how correct was his prophecy when he thus wrote.

The war came, and the various regiments departed, but little news of the course of events in France reached Hong-Kong for some time. The tenseness of war was lessened by distance, as this letter from him to a friend who had left Hong-Kong shows: ‘We are in a state of much military activity. There are outposts everywhere, searchlights sweep the harbour, every one is in khaki, no one can leave for Macao without a permit from the Provost-Marshal. The harbour is closed, battleships creep in and out, all the Empress boats have been painted battleship grey, the price of food has gone up, and we get no news of the war. So now you know how Hong-Kong stands.’

He knew well that for him it was quite useless to attempt to get into the Army by ordinary channels, in any capacity, medical or otherwise, on account of his heart. His one hope was to evade all medical boards, and slip in somehow. In 1915 he made repeated efforts to be appointed as Medical Officer to home-going battalions, whose Regular M.O.’s had been recalled. He all but attained this, but at the last moment Regular officers from India were appointed, to his bitter disappointment. He was greatly saddened by the death of his cousin, Captain Dalmahoy, 40th Pathans, who was stationed in Hong-Kong when Allan arrived there. The heavy losses of this regiment, to which he had hoped to be attached as M.O., filled him with sorrow. Dr. Fitzwilliams left for home to join the R.A.M.C., and Allan worked on valiantly, struggling with ill-health and overwork.

He wrote to an officer of the 126th Baluchistan Infantry: ‘It was good of you to remember this heart-broken devil out here and send him a line. I appreciated it more than I can say, but life is one long rush from dawn to dusk, and I have not written a letter to a soul for weeks and weeks, partly because quite a number of folks I would like to write to are absorbed out of all ken in the turmoil of this great affair, while many another has solved the riddle of life.

‘For a week I was going with the 40th Pathans as M.O., when H. ousted me. Then for a month I was going as M.O. to the 26th, when J. ousted me, then C. went off – that put the lid on it and spoilt all my chances of getting away. It was no use my going home with my rotten heart. I did my best to get a job, but I shall hate myself for evermore all the same.’

At the moment of writing, in June 1915, he was still suffering from a severe attack of dysentery which was immediately followed by appendicitis, for which he was operated on in the French Hospital. Ten days later he says: ‘I have got the appendix out and am very fit, taking it all round, though I am not exactly keen on going through it all again. Still it is a great experience, and one learns a lot of little things that will be useful in the treatment of others. Now I am waiting until it joins up, and then as soon as I can travel, will go up to Japan and lie quiet in some out-of-the-way spot.’

As soon as he was fit to be moved, he was carried on board ship and taken north to Japan to recover. He lay on deck during the voyage, feeling more dead than alive, and later was carried up country in Japan to a tiny inn beside a remote and lovely lake, renowned for its fishing by the few who knew of it. For days he lay beside the lake, far too ill to touch a rod, well tended by the gentle, kindly people of the inn, until slowly he recovered strength and drank in the absolute peace and beauty of mountain and lake. Afterwards he fished, and by his account, never was there such fishing! He then crossed to Pekin, and after wandering about for some little time longer, regaining strength, he returned to work in Hong-Kong.

It is difficult to give any succinct account of his doings at this period. He was at the full height of his power, and was straining it to the utmost degree, but he wrote no letters, and his friends had mostly left Hong-Kong, so it was only occasionally and from casual acquaintances that news came of the stupendous amount of work he was accomplishing, and of what a force he had become in Hong-Kong.

And so he continued to work and to fret because he was not at the Front, until 1916, when he started for Northern China to recruit coolies for labour battalions in France, a very difficult piece of work which he executed admirably, and which was only possible because of his aptitude for languages, as he had to learn an entirely new dialect in each recruiting area to which he was sent.

To a Hong-Kong friend he wrote: